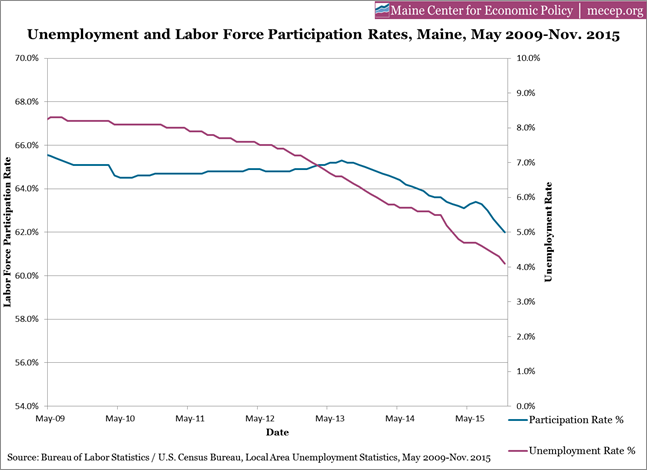

State Commissioner of Labor Jeanne Paquette today released the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) statewide workforce estimates for November. The headline touts a drop in unemployment to 4.1%, “the lowest since 2002.” If this appears to be cause for celebration – not so fast. Although the number of unemployed workers in Maine has been dropping steadily over the last five years (from a high of 58,000, or 8.3% in May 2009), this is mirrored in the BLS data by a decline in the labor force participation rate – the number of people actually looking for work. In other words, not all of the 30,000 people removed from the unemployment count since May 2009 have found jobs; some may have simply stopped looking.

In fact, the decline in the labor participation rate over that same time has been significant. 19,000 people left the civilian labor force; while employment increased by only 11,000. Nearly 2/3 of the responsibility for the decline in unemployment therefore lies with individuals giving up their search for work.

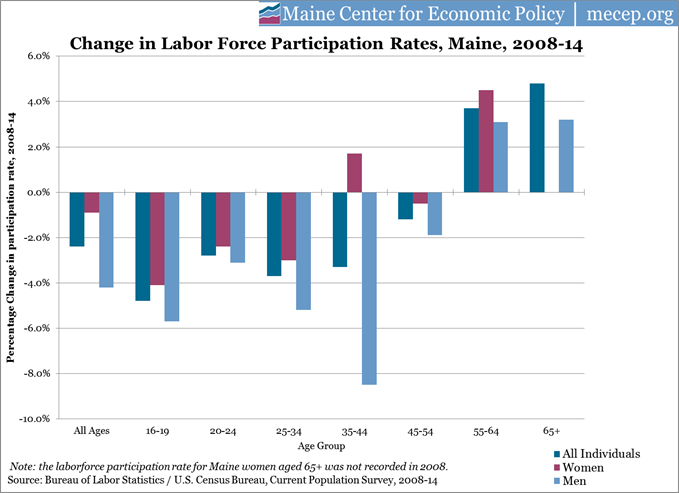

But wait, Maine has an aging population. Perhaps those 19,000 are just baby boomers reaching the end of their working careers, and settling into happy retirement? BLS data tell a different story. Between 2008 and 2014 (the most recent year for which information was available), the labor force participation rate declined across all age groups for both men and women – except for those aged 55-64 and those 65 and older. So while Maine’s population is aging, Mainers aren’t retiring at the rate you might expect.

The biggest drop in Maine’s labor force participation came from the youngest workers, those aged 16-19, as well as those who should be the backbone of the state’s economy – those aged 25-35, and those aged 35-44. Men were particularly affected – the labor force participation rate for men aged 35-44 dropped 8.5% from 2008 to 2014, representing 19,000 potential workers no longer seeking employment. The closure of several large Maine manufacturers since the start of the Great Recession is likely a significant factor in this trend.

The fact that total labor force participation by women is only down modestly over this period perhaps has implications for child care in Maine – but it also demonstrates the shift in Maine’s economy to so-called jobs still predominantly occupied by women – especially health care, education and hospitality. Overall, the discouragement of younger workers may be due in part to a possible “crowding out” effect (the subject of some contention), in which the propensity of older workers to remain in their jobs longer leaves fewer entry-level jobs available for 25-44 year-olds.

Maine’s economic growth remains sluggish. Celebrating today’s unemployment figures would overlook important long-term shifts in the economic landscape and trends in labor force participation. There is a much more important and troubling story behind that headline.