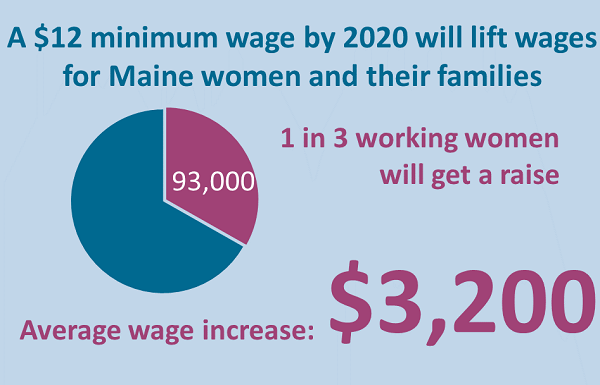

This November, Mainers will vote on an initiative that would gradually raise Maine’s minimum wage from $7.50 to $12 an hour by 2020. The effects of the initiative would be broad, including raising wages for 1 in 3 working Mainers by 2020 when the $12 minimum wage would be fully phased in. But, the advantages it offers for Maine women of all ages, including seniors and young girls, are especially important.

(Sarah Austin is the principal researcher of Restoring the Value of Work, MECEP’s report on our research and analysis of the minimum wage referendum)

The minimum wage initiative will improve opportunities for working women to save for a retirement that keeps them out of poverty and improve opportunities for low-income children around the state. Increasing the minimum wage to $12 per hour will also put an additional $300 million dollars a year in the pockets of working women across Maine, money they will likely spend locally, giving a boost to Maine’s economy that will benefit us all.

Wage income makes up nearly 60 percent of the income for Maine seniors.[i] The proposed minimum wage increase will raise wages for nearly one in three working seniors. This not only improves the immediate incomes of seniors, but will also improve their social security benefits as social security is based on lifetime earnings.

In 2014, the poverty rate for senior women in Maine was more than one-and-a-half times higher than the poverty rate for senior men, and, for Mainers 75 and older, the poverty rate for women was nearly double that of men.[ii] Contributing to these different rates of senior poverty is a persistent problem we have in Maine and across the country of women receiving unequal pay for equal work. Today, median wages for Maine women working full time are $9,000 less a year than the median full time wages for men.[iii] Over a 40-year career, that means a loss of $360,000 in earnings that would improve retirement savings and boost income.

A higher minimum wage can help. By 2020, a $12 minimum wage will increase earnings by an average of $3,200 a year for 93,000 working women in Maine. This will significantly lift a woman’s earnings over a lifetime and will substantially increase the amount of social security she is entitled to when she retires. A $12 minimum wage will also positively improve the opportunities women are able to provide for themselves and their families in terms of health care, transportation, and saving for the future.

When it comes to families, a $12 minimum wage in Maine would be transformative for working low-income families with young children. One in four Mainers who get a raise under a $12 minimum wage supports at least one child, making this initiative particularly important for the well-being of Maine children, including the nearly one in four girls under the age of five who live in poverty[iv]. A large body of research shows that children raised in poverty are less likely to be born healthy, less likely to show up to school ready to learn, and more likely to earn less as an adult compared with their peers.

For girls growing up in low-income families, the long-term impacts of poverty compound the effects of a wage system that pays women less than men for the same work. Increasing Maine’s minimum wage will immediately raise wages for a third of all working women. But the long-term impacts of the minimum wage for low-income families with small children are even more encouraging. A $12 minimum wage would increase family income by more than $3,000 for thousands of low-income families across Maine, and that means a better economic future for hundreds of Maine children. Research shows that young children in such families will realize an average 17% increase in their lifetime earnings.[v]

Maine’s economy thrives when women of all ages have opportunities to prosper. A $12 minimum wage will bring Maine closer to an economy that works for everyone.

[i] MECEP defines ‘seniors’ as Mainers 65 and older; University of New Hampshire, Carsey School of Public Policy. (2015). “Official Poverty Statistics Mask the Economic Vulnerability of Seniors: A Comparison of Maine to the Nation”. Available at: https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/vulnerability-of-seniors.

[ii] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. Poverty Status in Last 12 Months by Sex by Age, 5-yr estimates, 2010-2014.

[iii] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. Full-time, year-round civilian employed population 16 years and over by Sex, 5-yr estimates, 2010-2014.

[iv] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. Poverty Status in Last 12 Months by Sex by Age, 5-yr estimates, 2010-2014.

[v] Duncan, G., Ziol-Guest, K., and Kalil, A. (2010). “Early childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior and health”. Child Development, 81(1), 306-325. Available at: http://media.eurekalert.org/aaasnewsroom/2010/FIL_000000001525/Duncan%20Ziol%20Guest%20Kalil%20CD%20pdf.pdf.