A vibrant economy that works for everyone needs strong public services, and above all, good schools. And that requires everyone to pay their fair share towards those services. Recently, opponents of the voter-approved surcharge on high earners for education have sounded shrill warnings that Maine will be labelled a “high tax” state like Massachusetts or Connecticut. But the reality is that the alternative is far worse. Without investment in our schools and our economic future, Maine risks being labelled a “low opportunity” state, and will continue to see an exodus of young families, taking our economic future with them.

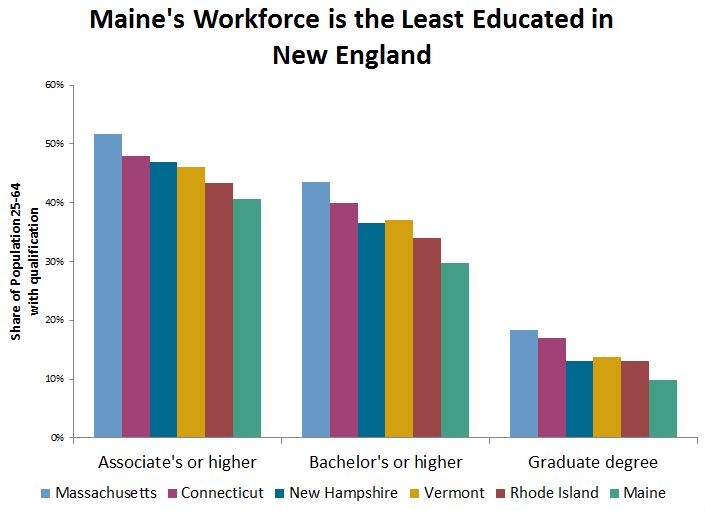

Maine consistently lags our New England neighbors in the education level of our population. Fewer Mainers have bachelors or even associate degrees than in any other state in the region. Without an educated workforce, employers can’t find the skilled workers they need to succeed. It’s also less likely that we will see home-grown entrepreneurs (the main source of job growth), as young Mainers leave the state for opportunities elsewhere.

Source: MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2011-15

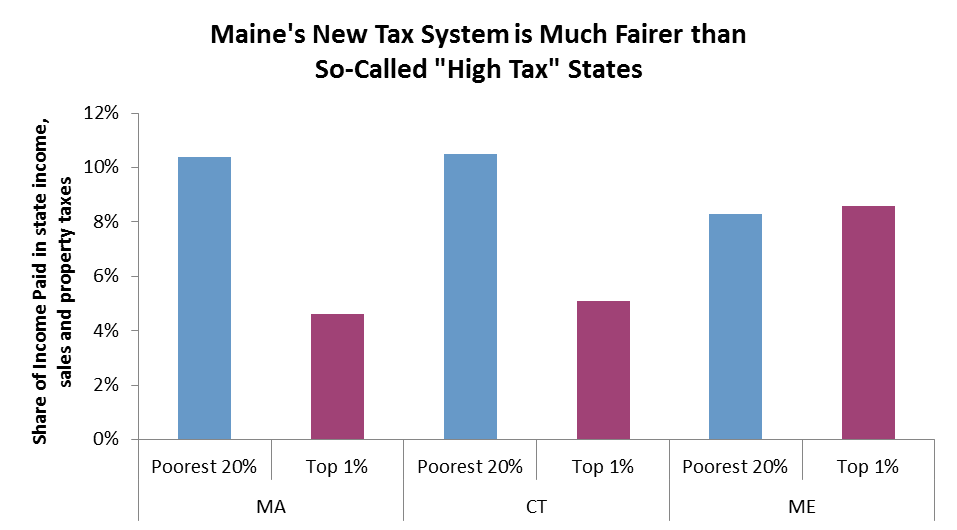

Massachusetts has the best public schools in the country. By some measurements, while the US as a whole lags the rest of the world, Massachusetts public schools are some of the best worldwide. It’s long been a hub for higher education, and the success of the “route 128 corridor” has made it the Silicon Valley of the east. None of that is possible without public investment in K-12 and higher education. What’s more, the label of “Taxachusetts” comes not from the state’s taxing high earners (it’s top rate of income tax has consistently been below Maine’s), but the share of taxes paid by lower– and middle-income residents of the Bay State.

Source: Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). Share of household income paid annually in state income, property, and sales taxes, after federal offset. Massachusetts and Connecticut data are for 2015. Maine data are for 2017 and include the effect of the education surcharge.

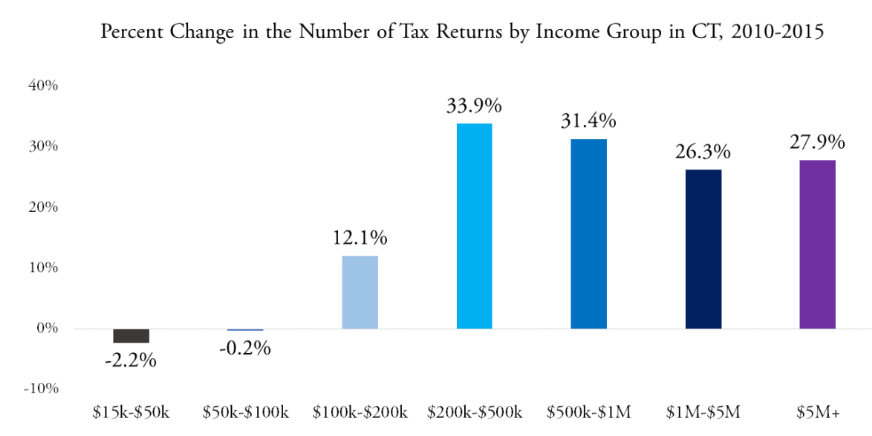

Meanwhile, Connecticut’s recent budget troubles have more to do with the lingering impact of the recession (which hit its insurance- and real estate-heavy economy hard) than anything else. The state has suffered net out migration in recent years, but primarily of lower income residents. The recent high profile departures of General Electric and Aetna – both of whom moved their corporate headquarters out of state- are not tied to the tax rate, but a lack of a skilled workforce. General Electric CEO Jeff Immelt, in announcing his company’s move cited “talent,” as well as “quality of life for employees [and] connections with the world.” GE also placed an emphasis on research and development spending and the presence of “a diverse, technologically fluent workforce.” And the company moved its headquarters not to “live free or die” New Hampshire, or some right-to-work state, but Boston.

Source: Connecticut Voices for Children/Connecticut Data Collaborative

And in Maine, we’ve seen a consistent pattern for years. Mainers leave the state in their late teens and twenties, only to return in their forties or to retire later in life. As a result, every year our birth rate falls, our population ages, and prospective employers find it harder and harder to hire skilled workers. Our economy has barely grown in real terms over the last decade. The status quo is unsustainable.

What ties Maine, Massachusetts, and Connecticut together is the relationship between state budgets and the well-being of their residents. Does Maine want to be a Massachusetts, with top notch schools, or a Connecticut, without the workforce to attract, retain, and create jobs?

Lawmakers have the opportunity to change Maine’s direction. Without investment in education and retaining our young families, Maine will face more decades, of economic stagnation. The fairest way to fund our schools – indeed the only realistic proposal on the table – is to ask the wealthiest 2% of households to pay a little more. The choice is clear and it’s now up to lawmakers to recognize this in their budget.