Maine’s hospitals can’t afford any more delays in accepting the federal offer to pay 90% of the costs associated with expanding eligibility to MaineCare. Medicaid expansion is necessary to avoid more hospital layoffs, but beyond the solvency of our hospitals, it’s necessary to ensure that Mainers have access to a doctor, that they can afford to see that doctor, and that they receive the care necessary to live long and productive lives. This November, Mainers can vote to accept the federal funding and increase access to MaineCare where the governor and legislature have failed.

Last year, half of Maine’s hospitals ran an operating deficit. According to figures from the Maine Health Data Organization, two thirds of Maine’s hospitals have just one month’s cash on hand (or less). Why is this important for Mainers? Not only are hospitals the primary providers of health care in the state, they are also the largest employers in nearly every county. For years, the Maine Hospital Association has warned about the financial strain on our hospitals, leading some to begin laying off staff, or shutting down entire departments. The major cause of this crisis is Governor LePage’s decision to not only refuse to expand Medicaid access under the Affordable Care Act, but to restrict Medicaid eligibility in Maine (known as MaineCare) – driving up the number of uninsured Mainers.

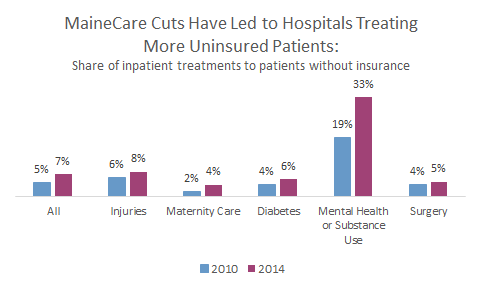

Uninsured patients are much more likely to be unable to pay for medical treatment, and leave hospitals with charity care costs or bad debt that they eventually write off. Data from the US Department of Health and Human Services, which maintains a database of state-by-state hospital inpatient admissions, show that Maine’s hospitals are seeing an increasing share of patients who have no insurance coverage whatsoever; a trend that coincides with a decline in the share of MaineCare admissions.

MECEP analysis of US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project data from the State Inpatient Databases project

Strikingly, this steady increase in the share of hospital patients without any insurance is consistent across diagnoses and treatment types. For example, even though MaineCare eligibility for pregnant women has not changed, there has been an increase in the proportion of maternity patients who don’t have insurance. This is consistent with the spillover effect of Medicaid cuts on other populations, like children, and may be a contributor to the recent rise in infant mortality in Maine, since uninsured mothers are less likely to have had pre-natal checkups and less likely to bring their children for post-partum care. The greatest change, however, has been in treatment for mental health and substance use. National data show that people living in poverty are twice as likely to suffer serious mental illness, and twice as likely to attempt suicide as other Americans. Among those treated for substance use disorder in Maine, 27% had no insurance and little to no income, making them especially likely to require charitable care.1

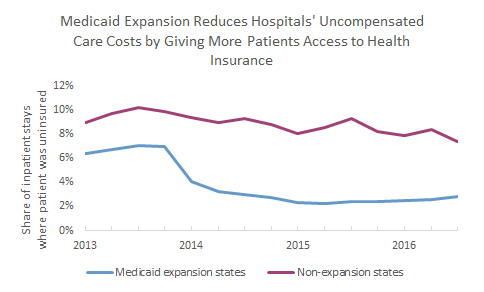

There is a clear solution to this growing problem that threatens the health of the tens of thousands of Mainers without insurance, and the solvency of Maine’s hospitals. Medicaid expansion will be on the ballot this November, and the effects of expanding eligibility to 138% of the poverty level (around $22,000 for a family of two) are well documented from the 31 other states which have participated so far. In Medicaid expansion states, the share of hospital treatments in which the patient had no insurance dropped dramatically when expansion was adopted in 2014 – from 7% at the end of 2013 to just 2% by 2016. Researchers at the Commonwealth Fund confirmed that hospitals in these states saw a 41% drop in uncompensated care costs as a result.

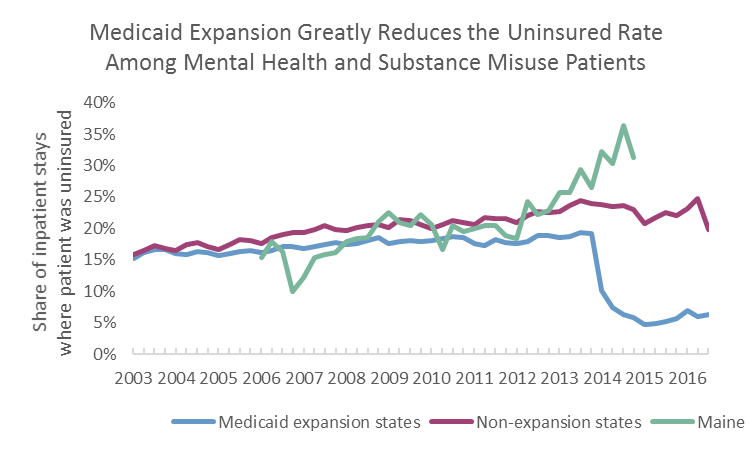

Once again, the effect of Medicaid expansion is greatest on those suffering from mental illness or substance use disorder. Since 2013, the share of mental health or substance use treatments, which were for patients without insurance, has dropped from 19% to just 6% in Medicaid expansion states, while it has remained relatively steady (at around 23%) in non-expansion states. The most recent data for Maine are from 2014, but even over the course of a year, the share of treatments that went to uninsured patients increased from 27% to 33%.

In other words, Mainers seeking mental health or substance abuse treatment are five times as likely to be uninsured than people in Medicaid expansion states.

Maine’s hospitals can’t afford any more delays in accepting the federal offer to pay 90% of the costs associated with expanding eligibility to MaineCare. Medicaid expansion is necessary to avoid more hospital layoffs, but beyond the solvency of our hospitals, it’s necessary to ensure that Mainers have access to a doctor, that they can afford to see that doctor, and that they receive the care necessary to live long and productive lives. This November, Mainers can vote to accept the federal funding and increase access to MaineCare where the governor and legislature have failed.

Note on Methodology

The data in this report from the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) are collected from state agencies and hospitals. To help protect the privacy of individuals and hospitals, treatment counts are rounded to the nearest 50. Therefore, the percentages presented in this report represent estimates, rather than exact counts. This is particularly true of the Maine data, where total quarterly treatment numbers are relatively small. Data represent treatments, rather than unique patients. The same patient may be represented twice if admitted more than once to a hospital.

Data from Indiana, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, which expanded Medicaid eligibility in 2015, were excluded. Lousiana, and Montana, which expanded in 2016, were treated as non-expansion states. Alaska and New Hampshire do not participate in HCUP.