Today, the presidents of Maine’s three public higher education systems reported to the Legislature on the state of their campuses, enrollments, and finances. The Maine Community College System (MCCS) report has been similar for several years – enrollments are up, but funding is flat. Allocating more resources to MCCS would remove a logjam restraining thousands of willing and qualified students across the state who are waiting to gain employment skills in high-demand fields– yet the Governor’s proposed budget would continue to flat-fund MCCS. In order to keep a lid on tuition increases, MCCS has been limiting enrollment in high-demand, high-cost programs including healthcare, construction and machine tooling – because there aren’t enough resources to hire more instructors.

Today, the presidents of Maine’s three public higher education systems reported to the Legislature on the state of their campuses, enrollments, and finances. The Maine Community College System (MCCS) report has been similar for several years – enrollments are up, but funding is flat. Allocating more resources to MCCS would remove a logjam restraining thousands of willing and qualified students across the state who are waiting to gain employment skills in high-demand fields– yet the Governor’s proposed budget would continue to flat-fund MCCS. In order to keep a lid on tuition increases, MCCS has been limiting enrollment in high-demand, high-cost programs including healthcare, construction and machine tooling – because there aren’t enough resources to hire more instructors.

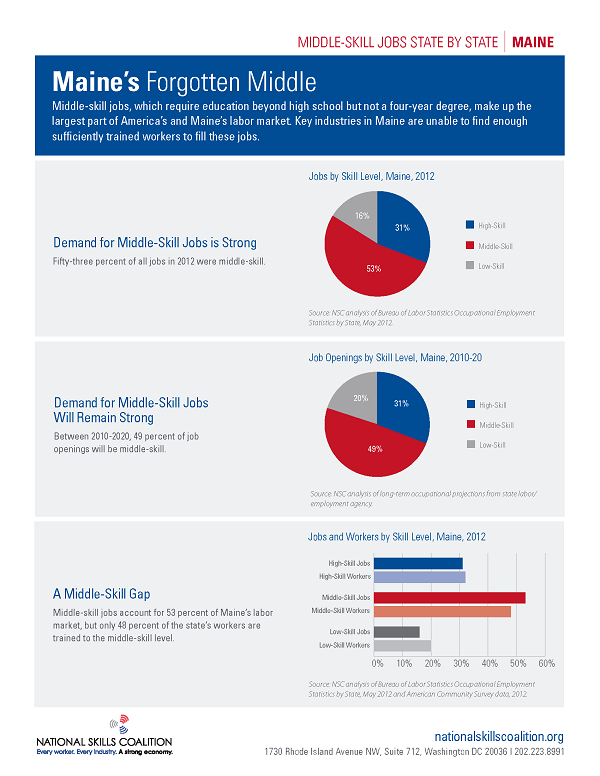

Middle-skill jobs – which require education beyond high school, but not a four-year degree – comprise more than half of Maine’s labor market. These are jobs in fields like nursing, high-skill manufacturing, and construction. All of these sectors are especially key to the economy in rural areas of our state, where healthcare and manufacturing are the largest employers in communities with otherwise persistently high unemployment. Maine’s middle-skills education pipeline, MCCS, charges the lowest tuition and fees of any community college system in New England – despite persistent underfunding. MCCS enrollment has increased eighty percent since 2002, but the legislature has increased state funding by only a third over the same period, with most of that increase taking place pre-recession.

Meanwhile, middle-skill job openings remain unfilled. Demand for these middle-skill jobs is strong, and will remain so for decades to come – but we don’t have enough qualified workers in Maine to meet the demand. Apprenticeships, which historically have been an important component of workforce development, have declined 36 percent since 1998 as union membership has declined steeply. In the meantime, Maine’s manufacturers report that they struggling to find qualified workers to fill these higher wage jobs. MCCS can partly fill the void left behind by the decline of apprenticeships. And it isn’t just manufacturers that would benefit from expanded community college capacity: most Maine employers are small Rbusinesses. As part of its rural Initiative, MCCS cooperated with small businesses to regionalize job training to meet their needs – pooling resources to deliver training employers could not have economically provided acting individually.

Meanwhile, middle-skill job openings remain unfilled. Demand for these middle-skill jobs is strong, and will remain so for decades to come – but we don’t have enough qualified workers in Maine to meet the demand. Apprenticeships, which historically have been an important component of workforce development, have declined 36 percent since 1998 as union membership has declined steeply. In the meantime, Maine’s manufacturers report that they struggling to find qualified workers to fill these higher wage jobs. MCCS can partly fill the void left behind by the decline of apprenticeships. And it isn’t just manufacturers that would benefit from expanded community college capacity: most Maine employers are small Rbusinesses. As part of its rural Initiative, MCCS cooperated with small businesses to regionalize job training to meet their needs – pooling resources to deliver training employers could not have economically provided acting individually.

Expanding access to MCCS programs could also be transformative for individuals seeking better, higher paying jobs. Completing a two-year degree carries an average wage premium of 31 percent. Graduating from community college particularly benefits women, whose earnings increase by 39 percent after graduating. Community college degree holders also have significantly lower levels of joblessness than do those with only a high school diploma – particularly for graduates who obtain a vocational degree.

As wages and employment continue to languish outside Maine’s urban areas, a gap persists between the demand for middle-skill jobs and the supply of workers trained to a middle-skill level. Education at all levels is important to ensure that workers have the skills they need to secure good paying jobs. Community colleges are an important part of the solution. To increase prosperity and meet the stated needs of employers in the state, policymakers should fund MCCS at a level commensurate with its enrollment growth – and its vital importance to the state economy.