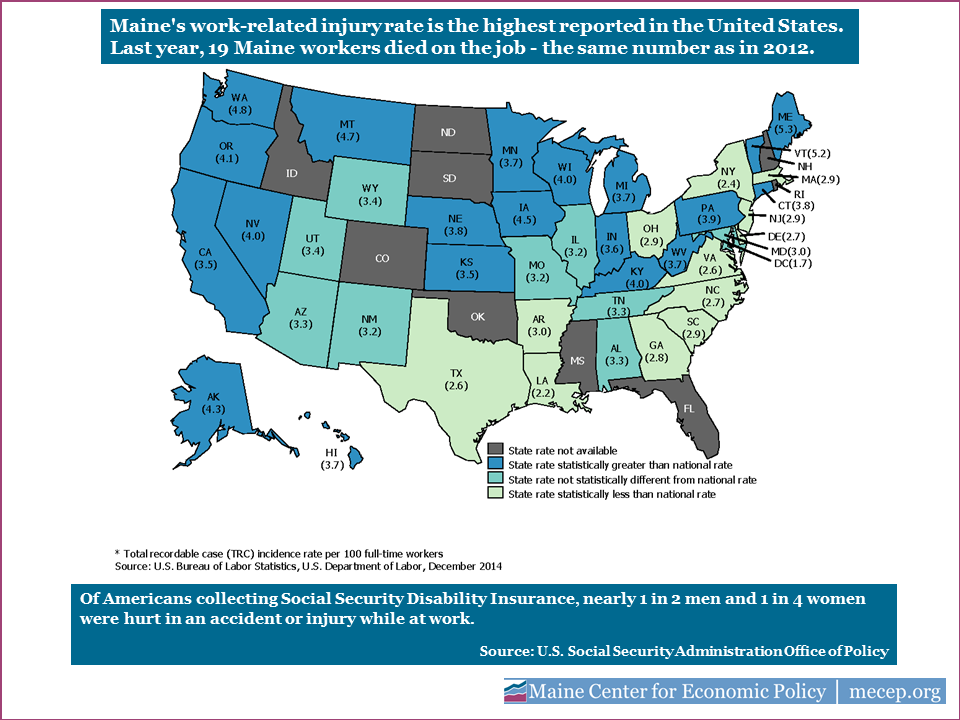

Workers hurt on the job have no lobby in the State House, so little fanfare accompanied the Bureau of Labor Statistics release on workplace injury this week. But of the states submitting data, Maine’s rate of worksite injury is the highest in the nation: 5.3 injuries or work-related illnesses for every 100 workers. Nineteen Maine workers died on the job in 2013. This data means a lot for our state economy and for the well-being of Maine’s workers.

Farming, fishing, and logging are core to Maine’s identity. They are also among the most dangerous of occupations. Growing up in the County, I was familiar with the stories of people’s hands crushed by fifth wheels on logging trucks, mangled in power take-offs, and dragged by a sleeve into potato house conveyors. I also knew people killed in farming and construction accidents, leaving behind grieving young families with no breadwinner.

Farming, fishing, and logging are core to Maine’s identity. They are also among the most dangerous of occupations. Growing up in the County, I was familiar with the stories of people’s hands crushed by fifth wheels on logging trucks, mangled in power take-offs, and dragged by a sleeve into potato house conveyors. I also knew people killed in farming and construction accidents, leaving behind grieving young families with no breadwinner.

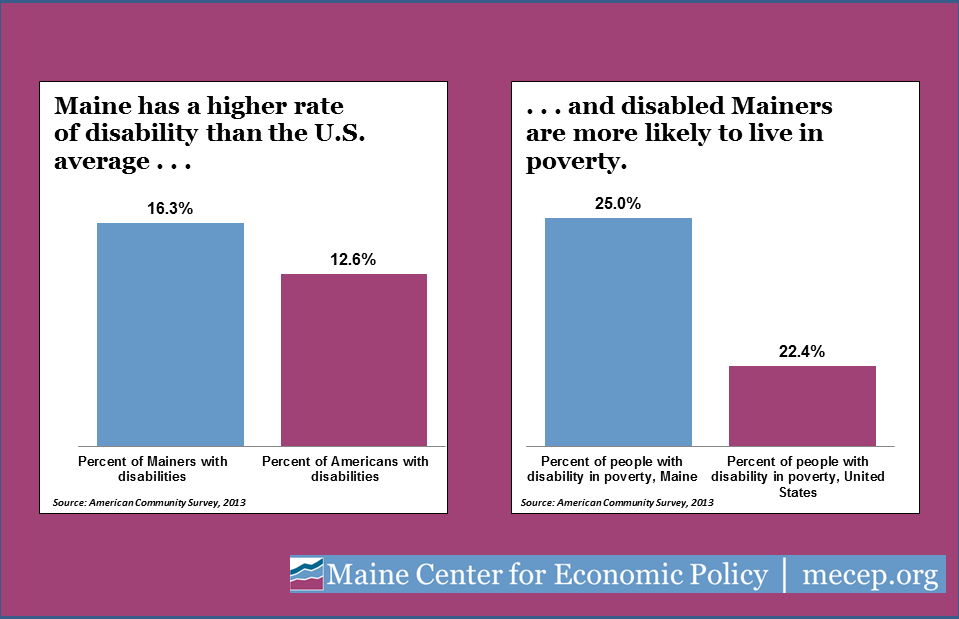

Nationally, nearly one in two men and one in four women with disabilities became disabled due to work-related injury or illness. More than 214,000 Mainers are living with a disability. Twenty-five percent of disabled Mainers live in poverty. Policymakers need to recognize that Maine has a higher-than-average disability rate, and that Mainers with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty than they would be if they lived elsewhere. Maine has the second-highest rate of disabled adults living in poverty in the nation– just behind West Virginia. Becoming disabled pushes people into poverty who otherwise might be securely middle-class. A moving piece on Vox.com recently described the difficulty a California family experienced after the mother was paralyzed in a car accident. After spending all of their savings, emptying their 401(K), and selling everything they owned except for their house and one car, the family qualified for California Medicaid – which would provide the daily care their mother needed to cope with paralysis. The family faced the prospect of never saving for emergencies, retirement, or college in order to secure the care their mother needed day-to-day. Recognizing that asset tests penalize the disabled and their families, about half of states have discarded asset tests for the disabled requiring Medicaid services. Maine still requires the disabled to have no more than $2,000 in assets.

In a state with a shrinking workforce, people with disabilities have much to contribute. The Maine Development Foundation suggests that as one strategy to combat a stagnating workforce, 10,000 Mainers with disabilities could join the workforce. Finding ways to make this happen so that individuals don’t lose vital health coverage and other supports – winding up worse off than before they took a job – is an important challenge for lawmakers.

Maine’s workplace fatality rate is unchanged from 2012. All of last year’s workplace fatalities were men, and twelve of the nineteen men killed were over 55. Nearly half of the fatal accidents were concentrated in farming, fishing, forestry, and construction. There are eight federal workplace health and safety inspectors in the entire state. It would take them eighty years to inspect every worksite once. Workplace fatalities are statistically rare, but to an individual family, they are too often world-ending. When policymakers target Temporary Aid to Needy Families or general assistance benefits for reduction or elimination, they should remember that they may catch families and children who are already suffering in their dragnet. And when politicians attack workers’ protections or rights to unionize to protect them against unscrupulous management or unsafe working conditions, all Mainers, not just those who lose benefits, stand to pay for it in lost productivity, a weaker overall economy, and a less prosperous Maine.

Maine’s workplace fatality rate is unchanged from 2012. All of last year’s workplace fatalities were men, and twelve of the nineteen men killed were over 55. Nearly half of the fatal accidents were concentrated in farming, fishing, forestry, and construction. There are eight federal workplace health and safety inspectors in the entire state. It would take them eighty years to inspect every worksite once. Workplace fatalities are statistically rare, but to an individual family, they are too often world-ending. When policymakers target Temporary Aid to Needy Families or general assistance benefits for reduction or elimination, they should remember that they may catch families and children who are already suffering in their dragnet. And when politicians attack workers’ protections or rights to unionize to protect them against unscrupulous management or unsafe working conditions, all Mainers, not just those who lose benefits, stand to pay for it in lost productivity, a weaker overall economy, and a less prosperous Maine.