The outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in the United States has triggered an unprecedented economic downturn. Businesses are closing, workers are losing their jobs, and families face a severe loss of income. As a result, many households are worried how to make rent or pay their mortgage.

Tens of thousands of residents may be at risk of eviction because of job losses associated with coronavirus. Many Mainers had a hard time affording housing even before the pandemic arrived in the state, with people of color at particular risk for housing insecurity as a result of systemic, race-based barriers to prosperity.

This week Governor Mills announced a “Stay Healthy at Home” order. But to stay home, families need to have a home. As state policymakers continue their efforts to protect Mainers from devastation in the wake of the pandemic, state action is necessary to assure secure housing for every Mainer.

Coronavirus did not cause housing insecurity, but clarifies urgent need for state response

Even before the pandemic, many families were just one illness, injury, or layoff away from missing the rent or mortgage. More than 160,000 households met the federal definition of “cost-burdened,” meaning that they paid more than 30 percent of their income for housing. Of these, 70,000 households are “severely cost-burdened,” meaning that they spent more than half their monthly income on housing costs.

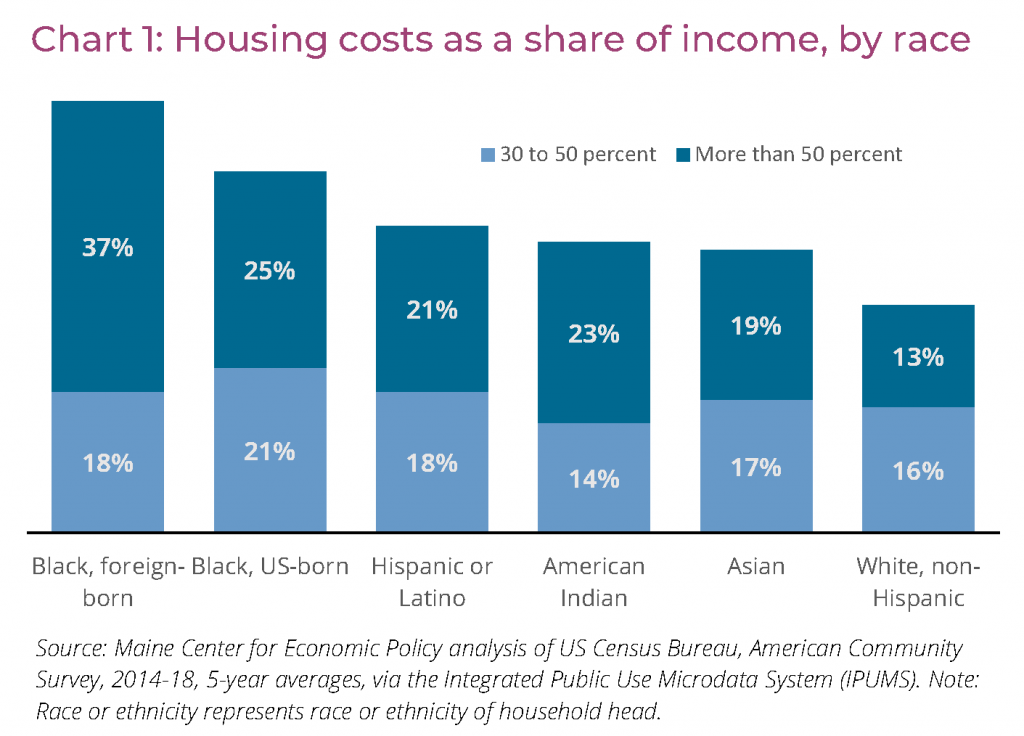

Mainers of Color are more likely to live in cost-burdened households than white Mainers, as a result of lower wages from systemic discrimination in education and employment. Renters are more likely to be cost-burdened than homeowners, and structural barriers to wealth accumulation and homeownership mean Mainers of color are more likely to be renters than white Mainers.

Our communities and economy are weaker when families struggle to make ends meet. But in the face of coronavirus, the shared effects of housing insecurity are starker than ever. When staying home saves lives, we’re all at increased risk so long as any of us can be evicted from our homes.

Cost-burdened families are especially vulnerable in this period of economic contraction. But the number of households facing economic crisis is growing fast. In late March, unemployment claims in Maine increased by 500 percent over the year before. Some estimates predict that 87,000 Mainers will be unemployed by July.

The state and federal governments have begun to address housing security as part of the crisis response. In Maine, state courts are closed for almost all eviction hearings. The federal government has announced a moratorium on foreclosures on federally backed mortgages and is prohibiting landlords with federally backed loans from issuing eviction notices. None of these measures is entirely adequate.

Rent and mortgage freeze would protect housing security for Mainers

Households need a rent and mortgage freeze to protect their access to housing for as long as the coronavirus makes normal economic activity unsafe. A broader program of forbearance would allow Mainers to skip mortgage or rent payments without suffering the penalties normally associated with nonpayment.

The federal government’s mortgage forbearance program only applies to about half of all mortgage holders. Some private lenders are agreeing to similar measures, but only on a case-by-case basis. Maine should require that all banks offer mortgage forbearance during the emergency period.

Renters, so far, have not received the same level of consideration from policymakers. Maine Governor Janet Mills has acted to prevent evictions during the length of the declared public health emergency. But simply delaying eviction proceedings or allowing landlords to collect multiple months’ rent after the emergency won’t solve the underlying financial hardship for Mainers. Without further protection, Maine could see a spike in evictions down the line when the moratorium ends, or renters could be asked to pay back several months of rent all at once — jeopardizing their ability to recover from weeks or months of lost employment.

A rental forbearance program at the state level would protect Maine renters and pair nicely with mortgage forbearance. Renters who have lost income would be protected from a loss of housing, while landlords who rely on rent payments to make mortgage payments on rental properties would be protected by the mortgage forbearance program.

The state could provide additional security to landlords who face economic hardship from uncollected rent payments during the pandemic (for example, those who would still be required to pay utilities, maintenance costs, and property taxes). Delaware already has a program to provide up to $1,200 a month in housing assistance to help cover rent and utility expenses, which is paid directly to property owners and utility companies.

Maine cannot forget residents already experiencing homelessness

While ensuring continuity of housing is critical, policymakers must also take action to protect Mainers experiencing homelessness during this public health crisis. Expanding shelter capacity — as the City of Portland has done by turning the Portland Expo center into a temporary shelter — would help protect Mainers who have nowhere else to go.

The state could also enact a temporary housing guarantee for people without any alternatives. Governor Mills has ordered Maine’s hotels, which rely on a robust tourism season, to close in all but select circumstances. A state program that paid for hotel rooms to shelter the homeless during the public health emergency would provide much-needed housing for vulnerable Mainers while helping Maine’s hotels weather a sharp decline in bookings. New York City already had such a program in place before the outbreak of COVID-19.