I will never forget one day when was in my late 20s, expecting my first baby. I happened to be alone with my grandmother in her tiny, gleaming kitchen. She paused, then asked gravely, “Now: have you put aside money for the hospital?”

“Well, not really, Grammy,” I stammered, perplexed by the question and her sudden seriousness. “We . . . we have health insurance to cover it.”

She accepted this with a nod, then added, “Well, when I was expecting, I picked potatoes that fall and put that money aside to pay the hospital.” I did a mental calculation that she must have been four months pregnant during the 1950 harvest. “That’s a lot of potatoes,” I remarked.

“Yup,” she agreed placidly, rose from her chair, and went back to wiping down the kitchen.

In the era when my grandmother picked potatoes to save for her labor and delivery, her case was not unusual. Pre-Medicaid or Medicare, slightly more than half of Americans 65 and older had private health coverage. Many other Americans had no or very inadequate private health coverage. Centers for Disease Control data for all ages in June 1963 found that approximately one-third of Americans did not have insurance to cover hospital stays or surgeries. The rest paid out of pocket—and the poor were far less likely to have any kind of coverage, and far less likely to get medical care. According to one survey from the early 1960s, one in four people reporting “pains in the heart” did not see a doctor; a third of people reporting “shortness of breath” put off care.

Poor children were much less likely to see a doctor, even if their symptoms were severe. The neonatal intensive care unit was introduced in the early 1960s, but since poor uninsured mothers were less likely to give birth in a hospital, some could not avail themselves of the technology. Babies born to poor mothers, as is the case today, were more likely to be low birth weight babies. But at the time, only nine percent of Americans with low incomes had insurance that would have covered prenatal care, and only a third had insurance that covered hospital stays.

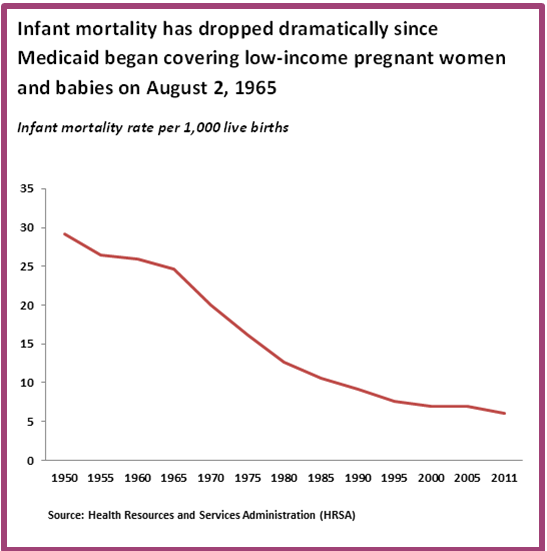

And then President Lyndon Johnson signed Medicaid into law on August 2, 1965, covering the blind, the disabled, and poor babies, children, and seniors. Pre-Medicaid, for every thousand nonwhite babies born in America, 30 died within a month of birth. For every thousand white babies born, 18 died within a month. The year Medicaid went into effect, infant mortality immediately dipped, and then continued to drop dramatically over the next decades.

America’s infant death rate remains too high compared to other developed nations, but Medicaid coverage has had a significant and dramatic effect on infant mortality. In 1970, oxygen deprivation at birth, respiratory distress syndrome, and influenza and pneumonia remained among the leading causes of infant mortality. Each of these often preventable causes of death fell a stunning 90 percent by 2007.

Sunday (August 2) marked the Medicaid program’s 50th birthday. My grandmother was healthy and strong when she picked a hundred barrels of potatoes a day in her youth: not all mothers and babies are so fortunate. With five decades of data, it’s no overstatement to say that Medicaid coverage has helped millions of the tiniest Americans blow out a candle on their first birthday cake, and kept millions of their mothers healthy and safe.