Since the Great Recession, Mainers’ personal incomes have grown at a slower rate than residents of nearly every other state, according to a new Pew Research Center study. The Pew analysis of data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis shows that the personal income of Mainers grew by an average of just 1.0% each year from October 2007 through March 2016. That’s the third slowest rate of income growth in the nation, and far below the US average rate of 1.7%. That means Mainers’ paychecks have barely grown each year for the past eight and a half years. In addition to concerns about the size Maine’s labor force, the failure of job numbers to rebound to their 2007 levels, and a reliance on part-time work, other recent analysis suggests a shift towards big business may be to blame.

A new study from the Roosevelt Institute examines the effect of the consolidation of the American economy since 2000 – the concentration of market power and employment in an ever-smaller number of large businesses. Since 2000, the rate of new start-ups has declined, and workers looking for employment or a new job increasingly find themselves limited to the same large, well-established corporations. The effect is to push down competition for labor and reduce the bargaining power of workers. The end result is to depress wage growth. As the study’s authors say:

“The evidence shows that employed workers are getting fewer offers to work at other firms, reducing their leverage to demand raises from current employers and leading to wage and earnings stagnation on the job … the data [also] show that percentage wage increases for job-switchers have either stagnated or declined.”

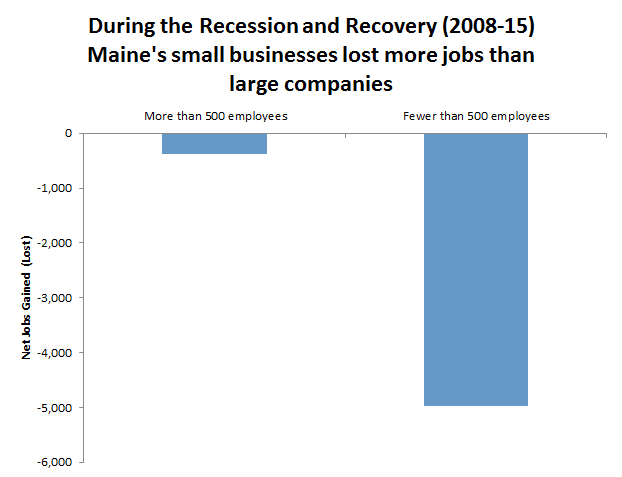

Maine’s post-recession economy has followed this trend. The dynamics of Maine’s economy have been shifting towards these large employers over the course of the Recession. It’s no surprise Maine’s wage growth has been so lackluster.

Source: MECEP analysis of US Bureau of Labor Statistics Data – Business Employment Dynamics, 2008-15

The study has broader implications for Maine than a decline in individual earnings. With its shrinking labor force, Maine desperately needs to attract more workers. But the effects of business consolidation have led to reduced mobility of workers, especially among the young. It’s no longer worth their while to move because it’s increasingly difficult to find a better offer of employment here than the job they already have. The Roosevelt Institute study explicitly rejects the idea that red tape and bureaucracy are the primary barriers to labor mobility, and point to wage stagnation instead. As The Economist noted in its coverage of the piece, another recent study from the Centre for European Economic Research in Mannheim, Germany, and the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands, looking at changes in the European economy, found that jobs lost from technological change could be mitigated or even outweighed by the benefits of these changes – but only if businesses re-invested their profits in the same economy. When large national and multi-national corporations send their profits overseas or out-of-state, the local economy suffers.

It’s no wonder then, that “big business a great majority of Americans distrust “big business,” A new Gallup poll found that only 19% of respondents trusted large corporations “a great deal” or even “quite a lot.” Addressing wage stagnation would go a long way toward restoring people’s faith in the economy. Maine needs to pursue policies that encourage new start-ups and small, local businesses which are the backbone of a healthy economy. More immediately, raising the minimum wage by voting yes on question four this November will provide a well-earned and much-needed boost to the paychecks of hundreds of thousands of Mainers and will ensure that those at the bottom of the wage ladder automatically receive an increase in line with inflation. Instead of stagnating, it’s time for Maine to thrive.