COVID-19 does not discriminate. Anyone exposed to the coronavirus can get sick, regardless of their race, ZIP code, or family income. Nevertheless, new data from the Maine CDC shows that Black Mainers are nearly four times more likely to get COVID-19 than white Mainers.

While there is likely no single, definitive cause for this disparity, it is clear that a system of underlying economic inequality and racial injustice is making the pandemic a more severe crisis for people of color.

In states and cities across the country where data can be broken down by race, a clear pattern is emerging: The pandemic is hurting Black Americans more than whites. Nationally, Black Americans are more likely to get COVID-19, to be hospitalized for their illness, and even to die. Other racial minorities, such as Latinx Americans, have also been contracting the virus at higher rates, and dying more often.

The newly released statistics from the Maine CDC are the first indicator of the spread of COVID-19 among Mainers of color.

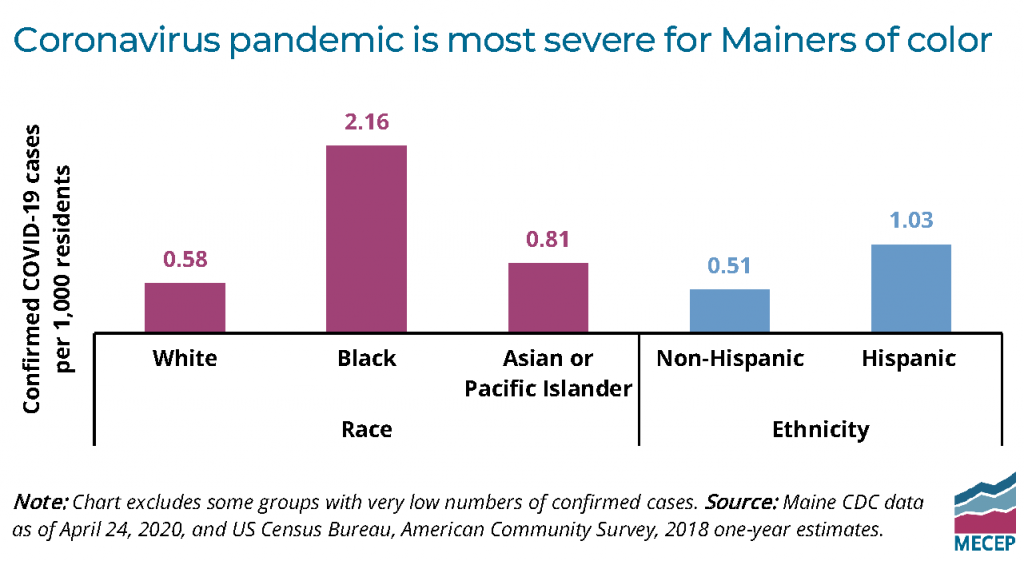

In proportion to the statewide population, Black Mainers are 3.7 times more likely to have tested positive for the disease than white Mainers, as of case data released on April 19. Mainers who identify as Hispanic tested positive at twice the rate of non-Hispanic Mainers, while Mainers from Asian and Pacific Islander backgrounds also had a positive test rate higher than the white population.

UPDATE: The Maine CDC is continuing to provide weekly estimates of confirmed cases of COVID-19 by race and ethnicity. As of May 27, the rate of infection compared to white Mainers was 18 times higher for Black Mainers than whites, and nearly twice as high for Asian and Pacific Islander Mainers. The rate for Latinx Mainers was 2.7 times as high as the rate for non-Hispanic Mainers.

Data from elsewhere in the country shows that Black people are affected by coronavirus at higher rates in urban and rural communities alike. For example, while cities have reported exceptionally high disparities between white and Black hospitalization and death rates, statewide figures also show a harsher impact on communities of color.

A host of pre-existing inequalities are likely coming together to make Coronavirus more deadly for people of color. A legacy of discriminatory public policies have saddled people of color with underlying health conditions that exacerbate the harm from the coronavirus. For example, housing policies that concentrate families of color in areas with more air pollution have led to higher rates of asthma and lung disease.

Racial disparities in the workforce are also undoubtedly increasing the likelihood that people of color will come into contact with the coronavirus. People of color and foreign-born workers in Maine are overrepresented in frontline industries such as groceries, health care, warehouses, and building cleaning and maintenance. In Maine, nearly one in five Black workers are employed at residential nursing homes,1 which account for a nearly a fifth of all reported COVID-19 cases.

To reduce the disparities that make this crisis far more deadly for people of color, we should ensure that frontline workers have adequate personal protective equipment and receive additional pay for the work they are doing. Those steps will reduce the likelihood of transmission and make it easier to afford health care.

Because our economy has left people of color more at risk to the virus, officials should also adopt public health measures specific to the Black and Latinx Mainers — in partnership with organizations led by people of color — including testing and triage centers in the places where those communities live.

To successfully end the epidemic and protect all Mainers, we must do more to mitigate the unique threat the virus poses to people of color. Disparities in our economic and health care systems are affecting the course of the pandemic. Addressing those disparities at their root with public policy can help ensure that all Mainers have an equal shot of recovery if they get sick.

Notes:

1 MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2014-2018 microdata using the Integrated Public Use Microdata System (IPUMS). Statistics for respondents with industry code 8290 (“residential care facilities, except skilled nursing facilities”).