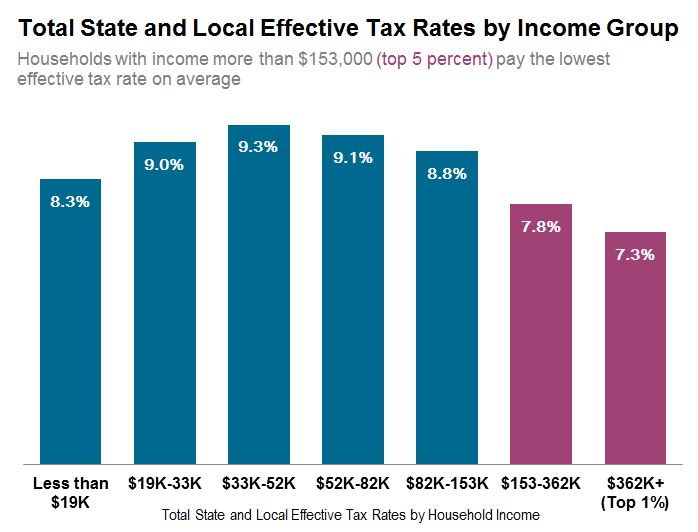

In the early hours of the morning on July 4th, Maine Lawmakers enacted a two year budget that repealed the voter approved three percent surcharge on household income over $200,000 and gave a massive tax cut to the top two percent of households. This is the third biennial budget in eight years that contained tax breaks for the wealthiest Mainers. The top five percent of Mainers now pay the lowest effective tax rate on average compared to all other income groups. These tax breaks for the wealthiest come at a cost to investments in thriving communities and worsen income inequality.

Communities need investment to thrive. Roads, schools, libraries, fire protection, foster care caseworkers, and public health nurses are just some of the needed investments that help ensure broadly shared prosperity—the kind that everyone can benefit from, not just those with the highest incomes. Broadly shared prosperity leads to a stronger overall economy than if only a small group of people share in the benefits of economic growth. Big tax cuts for the rich are expensive and mean fewer resources are available to improve Maine’s communities.

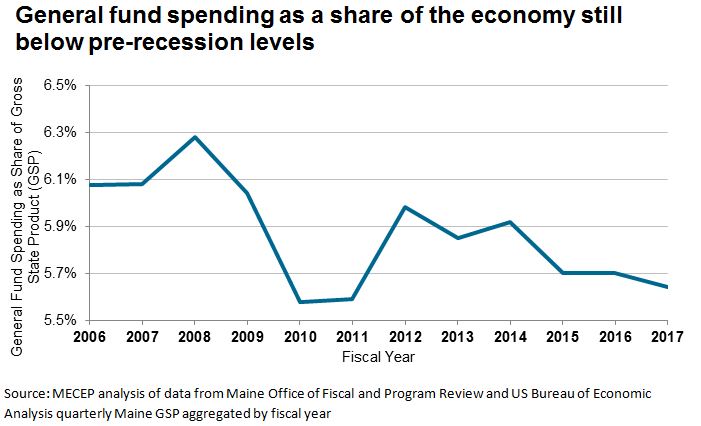

Maine still hasn’t returned to the level of investment it made before the Great Recession. Even though our economy has finally bounced back from the recession, Maine isn’t committing the amount of resources it typically does in good times. Instead, lawmakers cut services or squander new revenue sources to pay for more tax breaks. The impact of underinvesting is becoming clear in the data. Infant mortality is increasing, deep child poverty is increasing, and free and reduced lunch program participation is increasing. The youngest generation of Mainers is starting out with setbacks that can have lasting effects on their long-term ability to succeed.

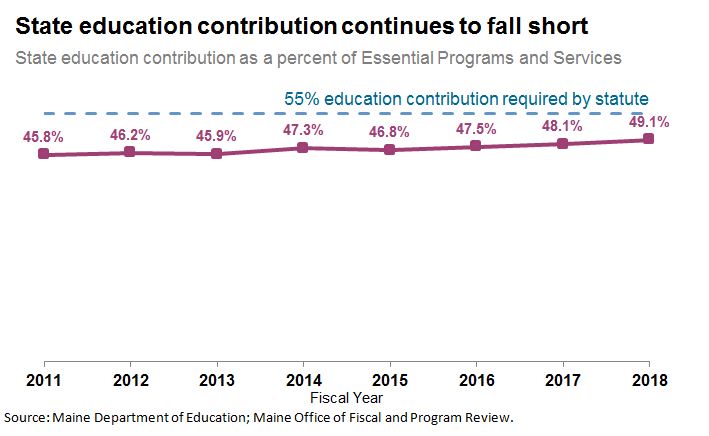

When the state invests less, local towns and communities often take on the responsibility of filling in the gaps in services left by state-level cuts. One of the most significant examples is when the state pays less than its 55 percent commitment to state-wide education costs, towns have to use more of their local budgets to supplement the school budget. This means increasing property taxes to fill in the gaps in state funding or making cuts in teacher positions or other town services.

The three percent surcharge would have made full funding of education within reach of this and future legislatures. With it repealed, Maine will only fund 49.1 percent of statewide education costs, rather than the 55 percent demanded by voters and codified in statute. The failure of this legislature to reach full funding means towns will still have to pay more than their share to provide a basic standard of education.

Property taxes are the largest source of revenue for local communities. When chronic underfunding by the state means constant pressure to increase property taxes, the tax code becomes less fair. Unlike income taxes, property taxes aren’t based on ability to pay. Low- and middle-income Mainers pay a higher proportion of their income in property taxes than wealthy Mainers.

Even larger disparities appear between property-rich and property-poor communities. Communities with a very high property value can raise a large amount of resources from very small adjustments in the mill rate, but communities with lower property values have to increase their mill rate by much more to raise the same amount of resources. That’s why a community like York can sustain high quality schools and services on a mill rate of 11.15 and Houlton, a town with a roughly a third of York’s property value per resident, has a mill rate of 22.25 to balance their budgets. Property-poor towns are less able to make up the difference when the state underfunds towns, which worsens geographic disparities in school and community services.

With the 3 percent surcharge repealed, the state’s tax code is out of balance. Those with the most are asked to pay the least. This means a middle-class family keeps 91 cents on average after state and local taxes for each dollar earned, versus 93 cents kept by the wealthiest in the state. This preferential tax treatment of wealthy Maine household also comes at a cost to roads, public health, and quality education that low and middle income Mainers rely on the most to succeed.

Source: MECEP analysis of data from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy; property, sales, and income taxes as well as federal tax offsets from state and local taxes paid depicted for a non-elderly population

This year, lawmakers cobbled together a non-sustainable package of onetime revenue sources from economic growth and lapsed funds to pay for their tax cuts for the wealthiest, but these funding sources won’t be available for the next budget. A more comprehensive approach to cultivating opportunity and thriving communities requires a new perspective on fair and adequate revenue. To get the healthiest kids, best schools, and safest infrastructure, lawmakers must be willing to ask wealthy Mainers to pay their fair share.