Contents

- Introduction

- A lagging economy leaves rural Maine behind

- Employment rates mask a troubling trend away from work

- Eroding middle-class jobs and growing inequality worsen economic outlook

- Persistent racial and gender inequalities deepen economic disparities

- Poverty and long-term unemployment are byproducts of Maine’s sluggish economy

- The unhealthy link between health and employment

- The path forward must move beyond the politics of austerity and race-to-the-bottom policies

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- End Notes

Downloads

Introduction

For decades, good jobs have sustained America’s middle class by paying decent wages and ensuring that workers have access to health care and retirement savings. A good job is essential to a decent quality of life, stable families, and, for many Mainers, access to health care. Maine’s economy also benefits when good jobs are plentiful and workers have the skills to attain them.

When average families can meet basic needs, provide a good start for their kids, invest in buying a home, retire with dignity, and spend a little extra at local businesses, the economy gets stronger. A thriving middle class also ensures that the well-being of the state’s economy isn’t consigned to a small proportion of the wealthiest families. Supporting good jobs by protecting the interests of Maine’s low- and middle-income families and investing in their futures is one of the most important roles policymakers must fulfill to ensure broadly shared prosperity and a strong economy.

A Great Recession and industry upheaval contributed to an economy that is failing to produce enough jobs with the pay and benefits needed to support Maine families. Too many Maine workers are still waiting for quality jobs to return to their communities. State lawmakers can chart a course to an economy made stronger through job creation, but to do so they must fully understand the challenges facing Maine workers and the obstacles to surmount for our economy to produce and sustain more good jobs.

The State of Working Maine 2017 presents a comprehensive analysis of the economic, demographic, and workforce trends that impact the quality and quantity of jobs in Maine. It provides data for policymakers to formulate policy solutions that will improve Mainers’ ability to find and secure good jobs that will reinvigorate our state’s economy.

A lagging economy leaves rural Maine behind

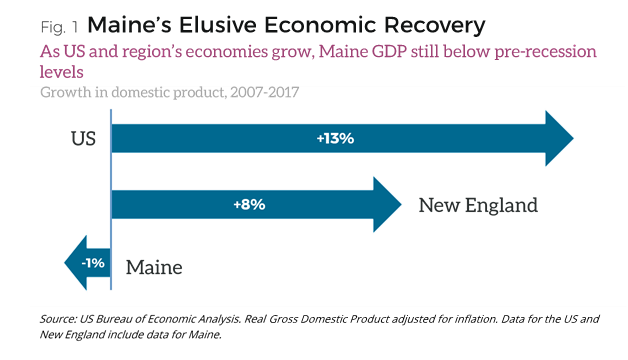

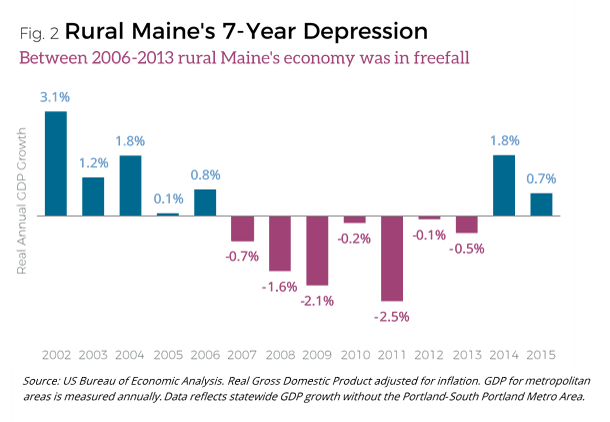

The performance of the state’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in recent years demonstrates the extent to which Maine’s economy has stalled out. Through the first quarter of 2017, Maine’s GDP had yet to recover to pre-recession levels, a distinction shared by just five states.[1] Maine has effectively suffered through three further recessions since the Great Recession of 2007-9. Two of these, in 2010-11 and 2012, met the traditional definition of a recession (two consecutive quarters of negative real-term GDP growth). During the third period, in 2015, Maine’s economy experienced no real-term growth over the course of a year. The result is an economy that underwent fitful periods of growth, followed by backsliding. Maine’s economy is still 1% smaller than before the Great Recession. By contrast the economies of New England and the nation are 8% and 13% larger, respectively (see Fig. 1). As limited as statewide economic growth has been, the real explanation for Maine’s failure to recover from the recession is found at the regional level in what has come to be known as the “two Maines.” In the Greater Portland metropolitan area, economic growth has been slow but consistent since 2009. Elsewhere, however, the economy has been in freefall. Between 2006 and 2013, GDP outside the Portland region fell for seven consecutive years, representing a severe economic depression for the rest of the state (see Fig. 2). In comparison, during the Great Depression of 1929, GDP contracted for just four consecutive years. A contraction of the economy on this scale represents very real hardships for hundreds of thousands of Mainers.

As limited as statewide economic growth has been, the real explanation for Maine’s failure to recover from the recession is found at the regional level in what has come to be known as the “two Maines.” In the Greater Portland metropolitan area, economic growth has been slow but consistent since 2009. Elsewhere, however, the economy has been in freefall. Between 2006 and 2013, GDP outside the Portland region fell for seven consecutive years, representing a severe economic depression for the rest of the state (see Fig. 2). In comparison, during the Great Depression of 1929, GDP contracted for just four consecutive years. A contraction of the economy on this scale represents very real hardships for hundreds of thousands of Mainers. The cultural, social, and economic differences between the “two Maines” are well-established, but from an economic perspective, this division may be more definitive today than ever before. The economy of rural and inland parts of Maine has diverged dramatically from that of the Greater Portland metropolitan area over the past decade. Rural parts of the state were more dependent on the large manufacturers that have downsized or closed, while the state’s economic center of gravity has increasingly shifted toward Portland. In 2001, the Greater Portland metropolitan area accounted for 48% of the state’s economy; by 2015, that share had increased to 51%.[2] This economic shift has been accompanied by the movement of people from rural to urban Maine. Between 2012 and 2015, the Greater Portland area received an annual net influx of 1,000 people relocating from other parts of Maine,[3] reinforcing the economy of the Portland area and depleting the workforce in the rest of the state.

The cultural, social, and economic differences between the “two Maines” are well-established, but from an economic perspective, this division may be more definitive today than ever before. The economy of rural and inland parts of Maine has diverged dramatically from that of the Greater Portland metropolitan area over the past decade. Rural parts of the state were more dependent on the large manufacturers that have downsized or closed, while the state’s economic center of gravity has increasingly shifted toward Portland. In 2001, the Greater Portland metropolitan area accounted for 48% of the state’s economy; by 2015, that share had increased to 51%.[2] This economic shift has been accompanied by the movement of people from rural to urban Maine. Between 2012 and 2015, the Greater Portland area received an annual net influx of 1,000 people relocating from other parts of Maine,[3] reinforcing the economy of the Portland area and depleting the workforce in the rest of the state.

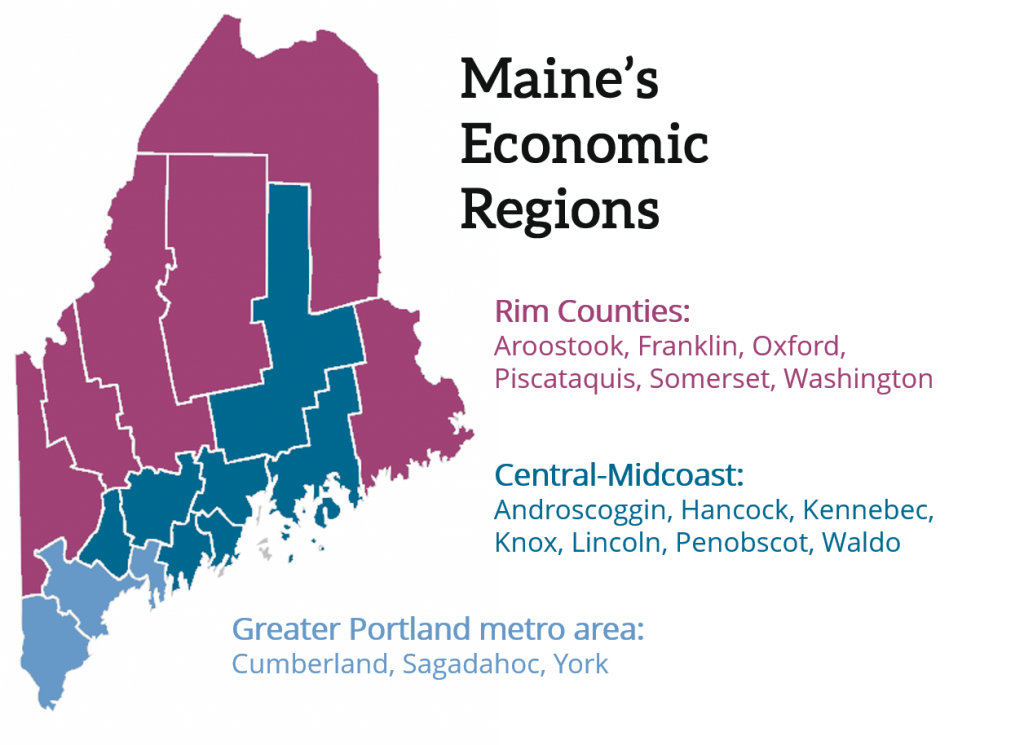

Variation also exists within rural Maine. Specifically, there is a marked difference in the economic conditions between Central-Midcoast Maine, and the “Rim Counties,” which border Canada and New Hampshire. The economic shock has been less severe in the Central-Midcoast region. Lewiston-Auburn, Bangor, and several other cities anchor this area, which also includes the University of Maine’s flagship campus at Orono, other colleges, and state government in Augusta. The Midcoast has a significant tourism sector, and sees a modest in-migration of retirees from other states.

The Rim Counties, by contrast, contain only small population centers, and their economies have traditionally relied on natural resources industries (particularly wood products). Maine’s failure to invest in its crumbling infrastructure has undermined new business and tourism in these areas.

GDP data are not available at the county level, but taxable sales data from Maine Revenue Services give some equivalent indication of economic performance. While taxable sales are up 3% in real terms in the Greater Portland area since 2007, they are down 3% in the Central-Midcoast region, and down 7% in the Rim Counties.[4] If the rural Maine economy as a whole is depressed, the Rim Counties’ economies are even more so.

Employment rates mask a troubling trend away from work

The most immediate impact of a sluggish economy on Mainers and their families is the effect on employment levels. In aggregate, Maine was one of the slowest states for employment numbers to recover to pre-recession levels. Total employment is just 2% higher in 2017 than a decade earlier.[5] However, gains in the Greater Portland area have compensated for slower recoveries elsewhere. In Central-Midcoast Maine, total employment is 1% higher than before the recession, while in the Rim Counties, it remains 3% lower.[6]

Maine’s population is the oldest in the US and has aged rapidly in the past decade. The average Mainer in 2015 was 45 years old,[7] up from 41 in 2005.[8] While this presents serious challenges for Maine’s economy, the aging of the state’s population, and therefore its labor force, does not fully account for the decline in labor force participation. In fact, older Mainers are working in greater numbers than ever before.

In 2001, just one in five Mainers between the ages of 65 to 74 was in the labor force; by 2016, that share had risen to one in three.[9] In part, this reflects the reality of modern “retirement,” in which most Americans must work as long as possible to compensate for inadequate retirement benefits. The majority of Maine seniors (53%) now has no retirement income beyond Social Security,[10] which provides an average income of less than $19,000 a year.[11] This is the result of a drastic shift in traditional employer responsibilities to their workers. In 2016, fewer than one in five (18%) American private-sector workers was able to participate in a defined-benefit retirement plan,[12] and one in three (34%) had no access to any kind of retirement plan through their employer.[13]

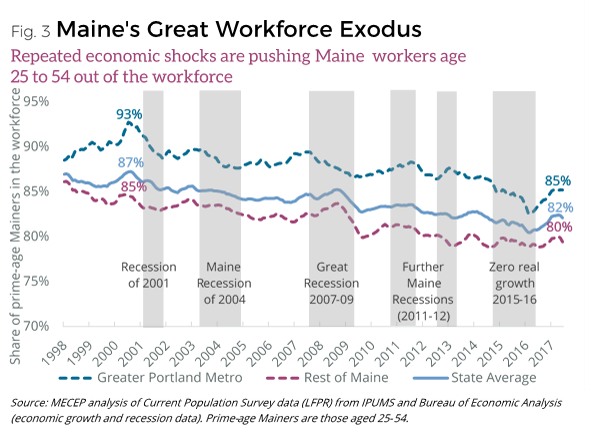

By contrast, the labor force participation rate among prime-age workers, those whom economists define as age 25 to 54, has fallen dramatically over the same period, from 87% in 2001, to 85% in 2007, to 82% in 2017 (see Fig. 3).[14] The five percentage point difference in labor force participation from 2001 to 2017 represents 30,000 Mainers of working age who are not participating in the economy, a worrisome figure for Maine’s workforce. The “headline” unemployment rate which is most often cited in the media, only includes those jobless Mainers who have actively sought work in the last four weeks.[15] If the unemployment figure included those 30,000 workers who have left the labor force entirely, Maine’s unemployment rate would be twice as high as it is today.

The five percentage point difference in labor force participation from 2001 to 2017 represents 30,000 Mainers of working age who are not participating in the economy, a worrisome figure for Maine’s workforce. The “headline” unemployment rate which is most often cited in the media, only includes those jobless Mainers who have actively sought work in the last four weeks.[15] If the unemployment figure included those 30,000 workers who have left the labor force entirely, Maine’s unemployment rate would be twice as high as it is today.

The difference in labor force participation among Maine’s older and younger workers helps to explain the paradox of Maine’s current headline unemployment rate being among the lowest levels on record while simultaneously the economy as a whole is in such poor shape. Policymakers who assume that a low unemployment statistic represents a strong economy are gravely mistaken. Maine’s low labor force participation is a problem for businesses unable to find the workers they need to sustain and expand their operations, and it is typically a symptom of greater structural problems in the economy.

Understanding why Mainers are dropping out of the workforce is key to identifying and addressing these structural problems and to moving toward an economy that works for everyone.

Individuals may opt out of the labor market for a variety of reasons. Some, such as attending school or raising a family, have an economic value that is not captured in the basic estimates of labor force participation. These individuals are equipping themselves for more stable employment or higher future earnings, or caring for family members. However, the share of prime-age Mainers attending school full-time has not risen significantly enough to explain a labor force drop. Another group opting out of work is the increasing share of Mainers who self-identify as disabled, but do not qualify for Social Security disability payments.

There is also a growing number of prime-age Mainers excluded from the labor force that current data do not include. For these Mainers neither education, family, health, nor retirement keep them out of the labor force.[16] Industry upheaval and a failing economy have impacted many of these Mainers’ relationships to work. Some have lost good paying jobs they were either unable to replace or forced to replace with lower paying jobs that undervalue their skills. Long-term unemployment or employment in positions that a worker is overqualified for set back a worker’s lifetime earnings and make it harder for such workers to secure a higher paying job when the labor market improves.

When previously employed Mainers find themselves in this situation, especially those who are older and worked in manufacturing, it becomes increasingly difficult to regain economic security especially when the path to a better paying job requires retraining or new skills that demand a four-year or post-graduate degree.

Eroding middle-class jobs and growing inequality worsen economic outlook

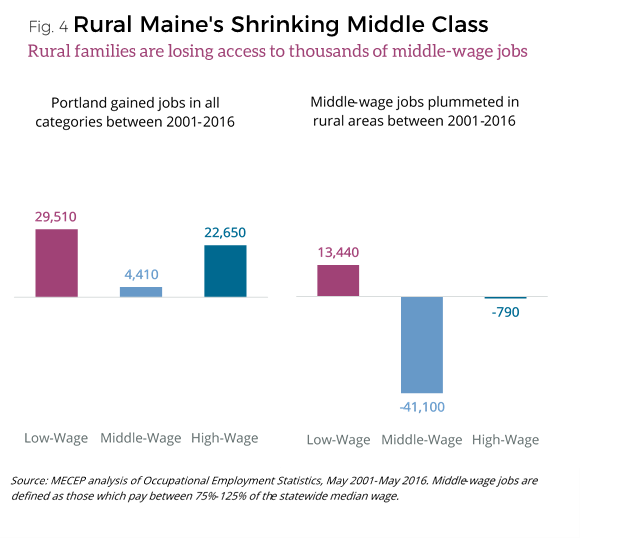

Maine’s slow job recovery rate since the 2007-09 recession is one cause of economic distress, but the quality of the jobs created after the crash has added to the problems of working families. Middle-class jobs―especially ones that, with relatively little training or education, could support a family, have disappeared in large numbers, while low-wage jobs, largely in service, retail, and tourism sectors have replaced them. This phenomenon began more than 15 years ago after the 2001 recession. Since then, Maine has lost a net of 37,000 middle-class jobs, mostly in manufacturing, largely replaced by low-wage jobs.[17]

While there has been some growth in high-wage jobs, the level of training, education, or experience required for these jobs (in sectors like education, health care, and technology) limits the ability of former manufacturing workers to access them. The decline of middle-class jobs has been particularly impactful in rural Maine, where even low-wage jobs have not replaced all the losses in manufacturing and other decent-paying industries (see Fig. 4). The decline in middle-class jobs has also led to a decline in the number of jobs that pay a living wage. According to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers, in 2016, the living wage for a Maine family varied from $10.33/hour for a single person living alone to $22.34/hour for a single parent.[18] The living wages the MIT team cited are based on a 40 hour-per-week, 52 weeks-per-year work schedule, and include the costs of food, housing, child care, health insurance, transportation, and other basic necessities.

The decline in middle-class jobs has also led to a decline in the number of jobs that pay a living wage. According to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers, in 2016, the living wage for a Maine family varied from $10.33/hour for a single person living alone to $22.34/hour for a single parent.[18] The living wages the MIT team cited are based on a 40 hour-per-week, 52 weeks-per-year work schedule, and include the costs of food, housing, child care, health insurance, transportation, and other basic necessities.

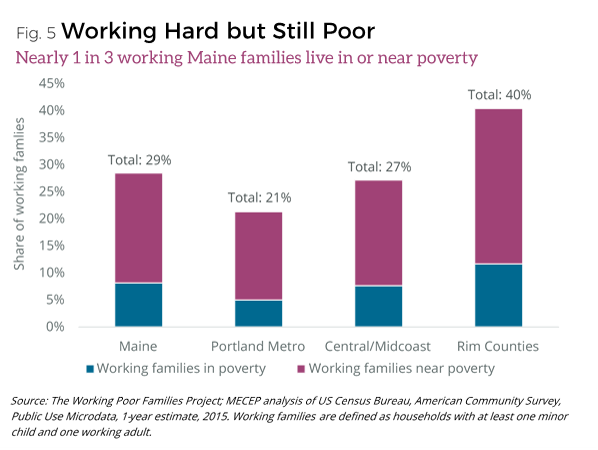

US Census Bureau data show that 38% of Mainers live in households in which wage-earners don’t make this living wage.[19] This means that large numbers of working Mainers and their families go without or scrimp on basic necessities like health insurance, adequate child care, food, or clothing. Some make up the difference by working longer hours, multiple jobs, or both―or by relying on extended family to care for children, aging parents, or others unable to care for themselves. But for many Mainers, the reality is that their jobs do not support a basic standard of living, and close to one in three of Maine’s working families lives below, or near, the poverty line. And of the working families in Maine’s Rim Counties, 40% are in the same situation of barely getting by (See Fig. 5).[20]

Wage stagnation has been a concern in the US for years. Real wages for Mainers in the middle of the income distribution increased just 3% in real terms between 2002 and 2016. For large sectors of the population, real hourly wages have fallen―as much as 3% for the lowest-earning decile. By contrast, wages for the highest-paid decile have risen 8% in real terms.[21] The impact of this inequality in wage growth undermines economic activity by reducing the ability of the lowest-earning Mainers who are most likely to spend additional earnings on goods and services from doing so.

Wage stagnation has been a concern in the US for years. Real wages for Mainers in the middle of the income distribution increased just 3% in real terms between 2002 and 2016. For large sectors of the population, real hourly wages have fallen―as much as 3% for the lowest-earning decile. By contrast, wages for the highest-paid decile have risen 8% in real terms.[21] The impact of this inequality in wage growth undermines economic activity by reducing the ability of the lowest-earning Mainers who are most likely to spend additional earnings on goods and services from doing so.

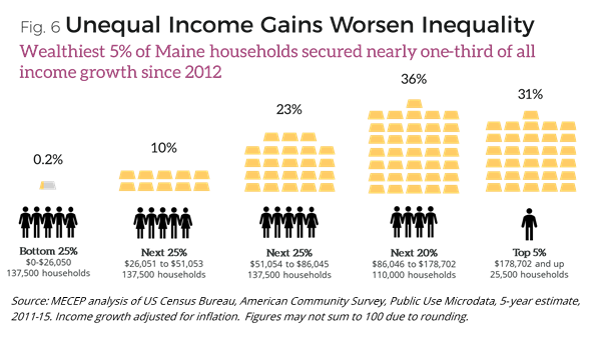

Maine’s post-recession economy has only widened the existing inequality between the wealthiest and poorest Mainers. In addition to the disparity in wage growth, the ability of the wealthiest Mainers to grow their income through investments (taxed at lower rates than wage income) has further increased income inequality. In the post-recession period, the value of shares on the Dow Jones stock index doubled.[22] Approximately 31% of all real household income growth between 2012 and 2015 went to the wealthiest 5% of Maine households, while the poorest 25% of households realized just 0.2% of the total income growth (see Fig. 6).[23] In the face of rising income inequality, little-to-no wage growth, and the disappearance of middle-class jobs, opportunities for Mainers have been drying up over the last decade. Two-thirds of Mainers who voted in the 2016 election said their family’s financial situation was the same, or worse, than it was in 2012;[24] while nearly four in five of Maine’s 2012 electorate said the same,[25] making it likely that a majority of Mainers has experienced no significant improvement in their family’s economic conditions since the recession began. Only one in three Maine voters in 2016 said they expect their children will have a better life than they have experienced.[26] This level of pessimism is exemplified in the increasingly common view (held by almost three-quarters of Americans)[27] that the economy is “rigged” to favor one group over another.

In the face of rising income inequality, little-to-no wage growth, and the disappearance of middle-class jobs, opportunities for Mainers have been drying up over the last decade. Two-thirds of Mainers who voted in the 2016 election said their family’s financial situation was the same, or worse, than it was in 2012;[24] while nearly four in five of Maine’s 2012 electorate said the same,[25] making it likely that a majority of Mainers has experienced no significant improvement in their family’s economic conditions since the recession began. Only one in three Maine voters in 2016 said they expect their children will have a better life than they have experienced.[26] This level of pessimism is exemplified in the increasingly common view (held by almost three-quarters of Americans)[27] that the economy is “rigged” to favor one group over another.

Contemporary and historic data show a vanishing window of opportunity for low-income Americans to advance economically. A landmark study by economists at Stanford, Harvard, and the University of California at Berkeley found that the chances of Americans earning more than their parents has plummeted from 90% for Americans born in 1940 to just a 50% chance―a coin toss―for Americans born in 1980.[28] The same study concludes that we cannot restore economic opportunity simply by encouraging economic growth; the increasingly inequitable way in which the profits of a growing economy are divided are the prime cause of the decline in opportunity.

Persistent racial and gender inequalities deepen economic disparities

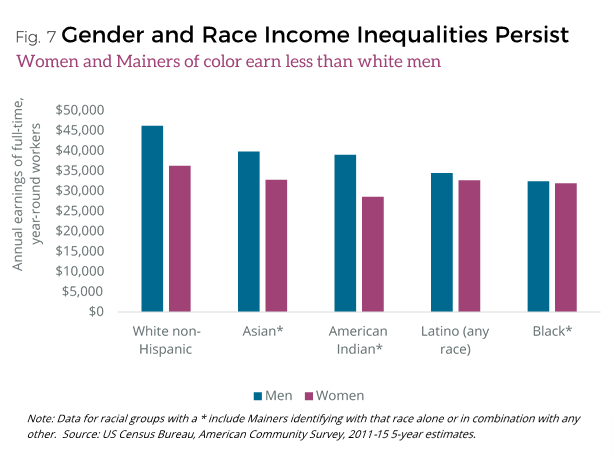

Along with the declining rates of economic opportunity for all Mainers, it’s important to recognize that the situation is worse for people of color and women (see Fig. 7). Maine women who work full-time, year-round, earn, on average, 79 cents for every dollar their male peers earn.[29] Maine’s “gender gap” is smaller than nationally, but Maine women, like women nationwide, have been trying to close this difference in earnings for more than half a century, since the passage of the 1963 Equal Pay Act. The differential between men’s and women’s wages in Maine has closed slightly over the last few years (in 2005, women earned 75% of men’s wages), but at the current rate of progress Maine women will not achieve parity until 2057. Furthermore, a reduction in men’s wages rather than a marked improvement in women’s wages accounts for some of the gap closure in recent years.

Maine women who work full-time, year-round, earn, on average, 79 cents for every dollar their male peers earn.[29] Maine’s “gender gap” is smaller than nationally, but Maine women, like women nationwide, have been trying to close this difference in earnings for more than half a century, since the passage of the 1963 Equal Pay Act. The differential between men’s and women’s wages in Maine has closed slightly over the last few years (in 2005, women earned 75% of men’s wages), but at the current rate of progress Maine women will not achieve parity until 2057. Furthermore, a reduction in men’s wages rather than a marked improvement in women’s wages accounts for some of the gap closure in recent years.

Similarly, full-time, year-round Maine workers of color[30] earn 85 cents for every dollar earned by white non-Hispanic Mainers.[31] Women of color earn 67 cents for every dollar earned by a white man.[32] Mainers of color also face structural economic inequities that restrict opportunity, like hiring discrimination. As a result, Maine consistently has some of the highest poverty rates for people of color; between 2011 and 2015, the poverty rate for Mainers of color was more than twice as high (28%) as for white non-Hispanic Mainers (13%).[33] The aggregate statistics for all Mainers of color mask wide disparities between minority communities. For example, nearly half (45%) of black Mainers live in poverty.[34] The unemployment rate for black Mainers with a bachelor’s degree is typically the same as white Mainers with just a high school education.[35] Mainers of color also lag behind in key economic indicators like business and home ownership.

To lift Maine out of its current economic slump, we must ensure that every Mainer, regardless of gender or ethnicity, can participate fully in the economy. That means creating an economy that works for everyone, irrespective of their race or gender. For example, paid family leave and mandatory sick time policies would reduce the penalties women pay for taking on caregiving roles. In the short term, stricter enforcement of employment, lending, and housing discrimination laws can address racial disparities. Over the long term, Maine must equip its public K-12 education system to meet the needs of students from diverse backgrounds and effectively prepare them to attend college.

Maine’s demographic challenges make attracting a variety of Americans nationwide, as well as immigrants from overseas, a necessity for future economic growth. Ensuring that Maine is welcoming and inclusive is critical to our state’s future.

Poverty and long-term unemployment are byproducts of Maine’s sluggish economy

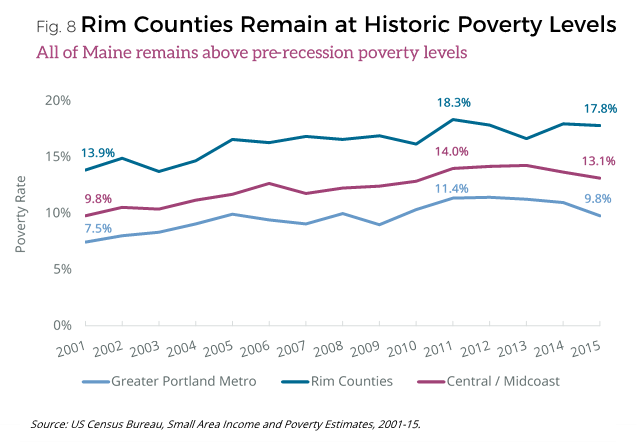

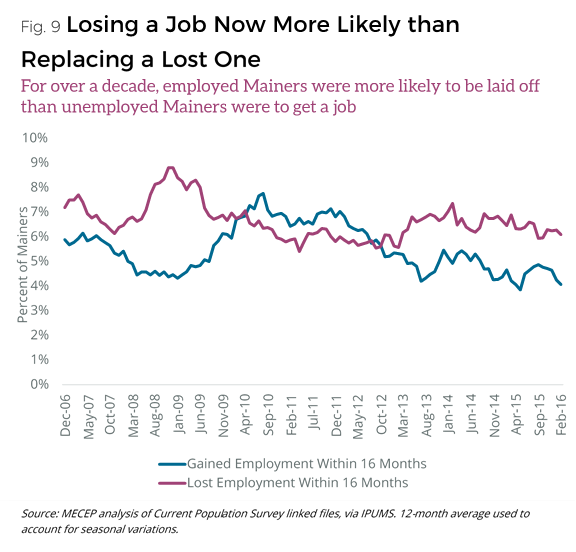

Maine’s increasingly unequal economy has also resulted in rises in both long-term unemployment (or labor-force nonparticipation) and poverty. Poverty rates outside the Greater Portland area are not only higher, but they have risen steadily since 2001. Between 2001 and 2015, the share of people in poverty rose from 14% to 18% in the Rim Counties, and from 10% to 13% in Central-Midcoast Maine. In these regions of Maine, the Great Recession pushed up poverty rates, and the lack of an economic recovery has failed to reduce them. Only in the Greater Portland area has the share of Mainers living below the poverty line fallen in recent years, from a high of 11% in 2011 to 10% in 2015 (see Fig. 8). Families typically move in and out of poverty due to volatile working conditions, but recent data suggest that the persistence of high poverty rates, and decreased participation in the labor force, are becoming chronic conditions. Between 2006 and 2017, movement in the labor force has been overwhelmingly in one direction―out of the labor force (see Fig. 9). Likewise, the share of prime-age Mainers out of work for more than five years has steadily increased since the onset of the Great Recession.

Families typically move in and out of poverty due to volatile working conditions, but recent data suggest that the persistence of high poverty rates, and decreased participation in the labor force, are becoming chronic conditions. Between 2006 and 2017, movement in the labor force has been overwhelmingly in one direction―out of the labor force (see Fig. 9). Likewise, the share of prime-age Mainers out of work for more than five years has steadily increased since the onset of the Great Recession. In 2017, one in eight prime-age Mainers reported they had been out of work for more than five years.[36] For these Mainers, returning to (or entering) the labor force will be extremely challenging, and will become even more so the longer they are unable to find work. Studies have found that the probability of finding a job decreases by 50% after just eight months of unemployment. [37]

In 2017, one in eight prime-age Mainers reported they had been out of work for more than five years.[36] For these Mainers, returning to (or entering) the labor force will be extremely challenging, and will become even more so the longer they are unable to find work. Studies have found that the probability of finding a job decreases by 50% after just eight months of unemployment. [37]

The unhealthy link between health and employment

Long-term unemployment and poverty present serious health concerns―both for individuals and their families and for the economy at large. Americans in poverty are twice as likely to suffer a serious mental illness or harbor suicidal thoughts than those significantly above the poverty line.[38] Americans who are unemployed or out of the labor force are also at increased risk of having serious mental health issues.[39] Forty-four percent (44%) of prime-age men not in the labor force takes pain medication on a daily basis, and the vast majority of them report that pain prevents them from working fully.[40] Non-elderly Maine adults in low-income households are twice as likely to have asthma or diabetes than other Mainers; they also experience higher rates of high cholesterol and high blood pressure.[41] It’s no surprise, therefore, that one in three (32%) low-income non-elderly adult Mainers describe themselves as being in “fair” or “poor” health―three-and-a-half times the rate (9%) among Mainers at other income levels.[42]

Whether chronic poverty and labor force nonparticipation are the prime causes of poor health, or vice versa, is unclear, but the trend is certainly cyclical. Without a good job, low-income Mainers have fewer options to treat existing health problems, and are more likely to develop new untreated conditions. Low-income Mainers without insurance forego many preventive care measures. They are more likely to smoke and less likely to control high cholesterol or be tested for transmittable diseases. Only one in four receives an annual flu shot.

At the most basic level, more than four in ten (42%) uninsured low-income Mainers skipped a doctor’s visit in 2015 because they couldn’t afford it, and one in four (28%) haven’t had a routine checkup in at least five years.[43] Preventive care rates are higher not only among higher-income Mainers, but among low-income Mainers with insurance. In other words, insurance, rather than income, is the primary reason many low-income Mainers lose out on care. Without insurance coverage, the health problems of low-income Mainers will only get worse.

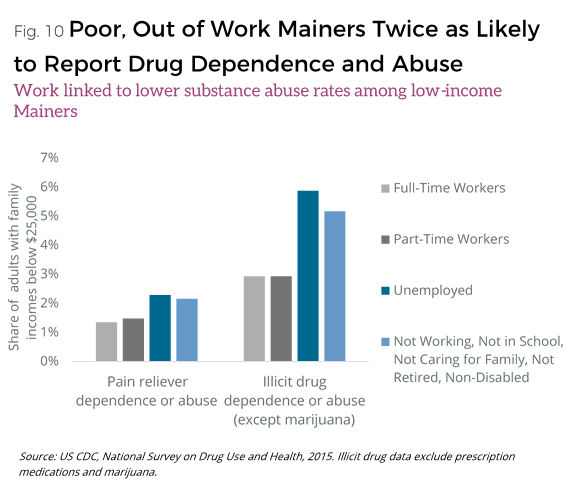

Caught in a cycle of poor health and lack of employment, Mainers are increasingly turning to alcohol and substance abuse. One in six unemployed Americans uses illicit drugs or alcohol, nearly twice the rate of employed Americans.[44] Prescription painkiller abuse rates are similarly elevated among the unemployed and non-working populations (see Fig. 10). The increase in chronic labor force non-participation has been accompanied by an increase in substance abuse rates and a growing epidemic of opioid overdoses and deaths. The latest national research suggests the two phenomena are intertwined. The research also verifies that higher rates of opioid prescriptions in states like Maine account for 20% of the decline in prime-age male labor force participation and 25% of the decline among women.[45] Applied to Maine, that model projects more than 5,500 Mainers aren’t in the labor force due to opioid abuse.[46]

The increase in chronic labor force non-participation has been accompanied by an increase in substance abuse rates and a growing epidemic of opioid overdoses and deaths. The latest national research suggests the two phenomena are intertwined. The research also verifies that higher rates of opioid prescriptions in states like Maine account for 20% of the decline in prime-age male labor force participation and 25% of the decline among women.[45] Applied to Maine, that model projects more than 5,500 Mainers aren’t in the labor force due to opioid abuse.[46]

As with other health conditions, it’s not clear whether opioid use led to labor force dropout or labor force dropout led to opioid abuse. There is certainly a lot of data to suggest that other factors pushed Mainers out of the workforce, and that Mainers who aren’t working display risk factors (like mental health disorders) for drug abuse. Regardless, there is clearly a cyclical effect between drug use and labor force non-participation.

As shown above, poverty and lack of work are strongly associated with a whole range of poor health outcomes, that hinder an individual’s ability to work. In addition, there are difficulties opioid abusers face in getting help and from the widespread use of drug testing as a hiring tool.

Opioid overdose deaths in Maine have greatly increased over the last 15 years ―up by 273% since 2010.[47] Prime-age Mainers who dropped out of the labor force have been dying in larger numbers every year for the last decade and a half. However, opioid abuse is not the only cause of this rising mortality.

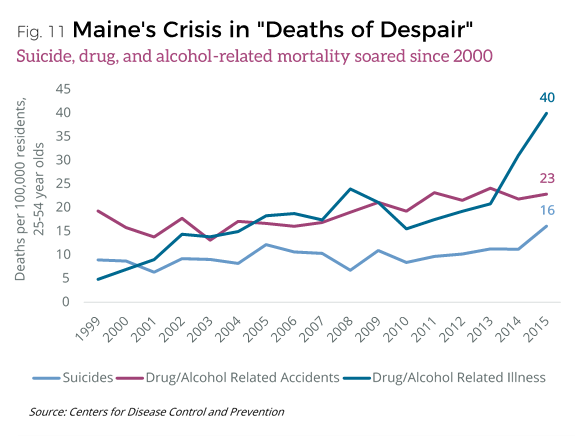

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show that among 25- to 54-year-old Mainers, between 2000 and 2015, suicide rates increased 45%, drug-related accidental deaths (e.g. overdoses) increased 577%, and deaths from drug- and alcohol-related illnesses (e.g. liver failure) increased 185% (see Fig. 11).[48] These deaths exemplify the phenomenon of “deaths of despair,” which has been observed nationally, especially among white, non-Hispanic working-class Americans.[49] The mortality rate among white non-Hispanic Mainers aged 45 to 54 rose 17% between 2000 and 2015. Over the same time period, it rose 7% nationwide, and remained steady in New England.[50] This rise in mortality is unprecedented after decades of improving health and life expectancy. It also makes the US an outlier in the developed world, where mortality rates continue to fall.[51] In total, the rate of “deaths of despair” in Maine increased 250% between 2000 and 2015 (from 30 to 80 deaths per 100,000 residents). Increases in New England and the US as a whole have been much less significant.

These deaths exemplify the phenomenon of “deaths of despair,” which has been observed nationally, especially among white, non-Hispanic working-class Americans.[49] The mortality rate among white non-Hispanic Mainers aged 45 to 54 rose 17% between 2000 and 2015. Over the same time period, it rose 7% nationwide, and remained steady in New England.[50] This rise in mortality is unprecedented after decades of improving health and life expectancy. It also makes the US an outlier in the developed world, where mortality rates continue to fall.[51] In total, the rate of “deaths of despair” in Maine increased 250% between 2000 and 2015 (from 30 to 80 deaths per 100,000 residents). Increases in New England and the US as a whole have been much less significant.

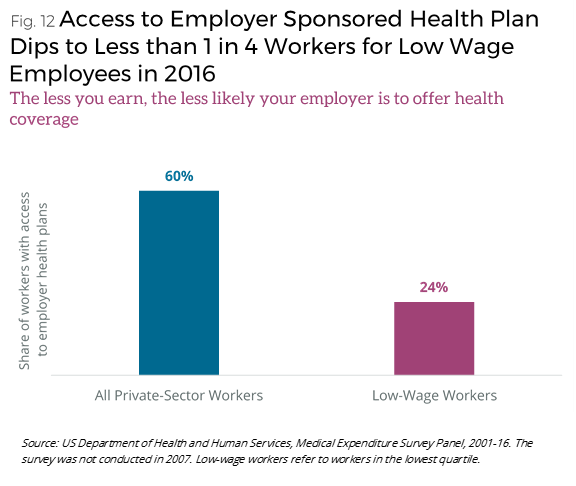

Even as mortality rates rise, traditional means of accessing health care like employment are becoming less available. Employers of low-wage workers are increasingly unlikely to offer health insurance plans to their workers. The share of low-wage private-sector workers eligible for a plan through their employer in Maine has fallen from 39% in 2002 to just 24% in 2016[52] (see Fig. 12).

Two factors help to explain this decline in the face of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s efforts to encourage employers to offer insurance. While nearly all (97%) Maine employers with 50 or more employees met the ACA’s mandate to offer an insurance plan, just one in four (27%) businesses with fewer than 50 employees (which are exempt from the mandate) did so.[53] Low-wage workers are more likely to be working for small businesses, especially in sectors like retail, accommodation, and food service.[54]

Two factors help to explain this decline in the face of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s efforts to encourage employers to offer insurance. While nearly all (97%) Maine employers with 50 or more employees met the ACA’s mandate to offer an insurance plan, just one in four (27%) businesses with fewer than 50 employees (which are exempt from the mandate) did so.[53] Low-wage workers are more likely to be working for small businesses, especially in sectors like retail, accommodation, and food service.[54]

Similarly, the ACA’s employer mandate only applies to full-time workers (those working 30 hours or more a week). While 91% of Mainers in these jobs were eligible for health insurance if their employer offered a plan, only 22% of part-time workers were eligible for their employer’s plan in 2016.[55]

The path forward must move beyond the politics of austerity and race-to-the-bottom policies

A decade after the start of the Great Recession, Maine’s workforce is still reeling. Not only is the size of the economy still smaller than before the recession, fewer Mainers are working and poverty remains at elevated levels. Maine families are feeling the effects of a lethargic economy. Wages are depressed, public health is failing, and lack of opportunity is causing young people to leave the state.

This state of affairs is not the result of bad luck, nor the whims of the larger US macroeconomy. Certainly, larger economic forces have played a role―the economic slowdown has been underway since the turn of the century, and in fact, Maine had not fully recovered from the 2001 recession before the bigger downturn in 2007. Maine’s decline in manufacturing jobs and shift to primarily low-wage service industries has meant lost wages for former middle-class earners and not enough jobs to go around. But that is not the full story.

The misplaced priorities of policymakers have undermined Maine’s current and future potential for growth. When, in the immediate aftermath of the recession, economic stimulus was called for, Governor LePage opted for austerity measures. Coupled with the end of the federal stimulus effort, this policy left Maine’s economy without much needed state investments in infrastructure, education, economic development, and other engines of growth.

Both as a share of GDP, and on a real-terms per-capita basis, state government spending in Maine is lower than it was before the recession. That means fewer services, less investment in infrastructure and education, and, ultimately, less economic activity. These long-term investments in Maine’s future are critical to creating an economy that works for everyone by equalizing opportunities within the state. A world-class K-12 and higher education system will allow every Mainer to reach their full potential, regardless of their ZIP code or the family they were born into; a modern system of highways, bridges, and broadband Internet will allow rural Mainers the same opportunities as those in the state’s cities. These same investments are crucial for encouraging business growth, vital communities, worker productivity, and overall economic robustness.

Instead, Maine has cut taxes and foregone billions of dollars in federal funding at the expense of our people and communities. Income tax cuts aimed at the wealthiest individuals and corporations have cost the state over $1 billion since 2011, for little noticeable economic gain. Maine’s Department of Transportation faces a $100 million annual shortfall just to keep up with maintenance needs on roads and bridges, but the state has foregone $82 million in revenue through cuts to the gasoline tax since 2012. Another $2 billion in federal grants and matching funds were ignored, misspent, or returned for various reasons by the administration between 2011 and 2017, a period in which the entire state economy grew an average of just 0.6% annually.

The phenomenon of Maine’s aging population and the story of “two Maines” have become easy excuses for policymakers to defend their failure to improve Maine’s poor economic performance. But this oversimplification obscures greater symptomatic issues in the economy, including the increasing prevalence of low-wage work, the lack of opportunity and rising income inequality, and a widening gulf between areas of the state made worse by policy decisions that undercut economic activity, infrastructure improvements, and health care delivery in many rural places.

An aging population presents its own challenges, but many of Maine’s economic problems are unrelated to these trends. The neighboring states of New Hampshire and Vermont, whose populations are similarly old, have achieved stronger economic growth than Maine.[56] Moreover, the weak economy encourages out-migration of younger Mainers, and exacerbates the existing demographic trend. In many ways, the aging of Maine’s population is a symptom, as much as a cause, of the stalled economy.

Now more than ever Maine needs to increase investments in our people and our communities to begin repairing the damage of past decisions. The path forward requires a commitment to leverage federal resources, reject costly tax cuts for the wealthy, and curb race-to-the-bottom policies that undermine our ability to invest in Maine’s economy. It requires leadership and vision to recognize Maine’s strengths and to harness them for the benefit of long-time residents and newcomers alike. Finally, it requires a willingness to pursue policies that foster greater opportunity and economic security for all Maine workers.

Conclusion

The State of Working Maine’s findings demonstrate the need for serious state policy solutions to restore the promise of good jobs, economic security for all Mainers, and opportunity for their fair share of future prosperity.

Over nearly a decade, New England as a whole and the US overall have bounced back from the Great Recession of 2007-09 while Maine’s economy has languished. During this period, economic disparities that existed even before the recession have gotten worse.

For Maine workers and communities, especially those already struggling to get by, the state’s poor economic performance and growing income inequality have taken a tremendous toll. Rather than force individuals and communities to go it alone and risk worsening economic conditions, the state’s economic challenges demand that Maine people and policymakers come together and build an economy that works for everyone.

Acknowledgements

About MECEP

The Maine Center for Economic Policy (MECEP) provides citizens, policy-makers, advocates, and media with credible and rigorous economic analysis that advances economic justice and prosperity for all Maine people. MECEP is an independent, nonpartisan organization founded in 1994.

About the Author

James Myall is MECEP’s policy lead on education, health care, and poverty and is a skilled policy researcher and analyst. He has a master’s degree in public policy and management from the University of Southern Maine and a master’s degree in ancient history and archaeology from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

About Our Funders

This report is published with the support of the Economic Policy Institute, Elmina B. Sewall Foundation, Ford Foundation, Maine Health Access Foundation, and Working Poor Families Project.

A Note About the Data

MECEP analyzed the US Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey data using the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) tool developed by Sarah Flood, Miriam King, and J. Robert Warren at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, 2015). Available online at http://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V4.0.

End Notes

[1] US Bureau of Economic Analysis, real GDP growth Q4 2006 through Q1 2017. In addition to Maine, the other states with negative GDP growth were Connecticut, Louisiana, Nevada, and Wyoming.

[2] US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Annual Real Gross Domestic Product.

[3] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2012-2015 data.

[4] Maine Revenue Services, Quarterly Table Retail Sales data. Comparison of sales data between Q4 2004 and Q1 2017, adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index.

[5] US Department of Labor, Local Area Unemployment Statistics, April-June 2017 average employment compared with April-June 2007 average employment.

[6] Ibid.

[7] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2015 1-year estimate.

[8] Ibid.

[9] US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2001-2016.

[10] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2015 1-year estimates.

[11] Ibid.

[12] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Employer Compensation Survey, 2016.

[13] Ibid.

[14] US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 3-month average April-June 2001 versus 2017.

[15] See https://www.bls.gov/cps/cps_htgm.htm for more detail.

[16] US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey.

[17] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Survey, comparison of 2001 and 2016 data. Low-wage jobs are defined as those in which the median wage for the occupation is less than 75% of the statewide median wage in that year; high-wage jobs are those paying above 125% of the statewide median.

[18] Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Living Wage Calculator. Available at http://livingwage.mit.edu/states/23

[19] MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey Public Use Microdata, 2015 1-year estimate. Household incomes were matched against the MIT living wage calculator’s estimate of the living wage for that household type.

[20] MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata, 1-year estimate, 2015.

[21] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics, Maine 2002-2016.

[22] Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis. Web. Available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DJIA

[23] MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata, 2011-15 5-year estimate.

[24] CNN exit poll, 2016 Web. Available at http://www.cnn.com/election/results/exit-polls/maine/president

[25] CNN exit poll, 2012 Web. Available at http://www.cnn.com/election/2012/results/state/ME/president/

[26] CNN exit poll, 2016. Web. Available at http://www.cnn.com/election/results/exit-polls/maine/president

[27] May 2017 poll conducted by Marketplace & Edison Research. Web. Available at https://www.marketplace.org/2017/04/24/economy/anxiety-index/you-think-washington-has-forgotten-you

[28] Chetty, Raj, et al.,” The fading American dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940,” Science, Apr 24, 2017. Web. Available at http://science.sciencemag.org/content/early/2017/04/21/science.aal4617.full

[29] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2015 1-year estimates. The Census Bureau defines full-time, full-year workers as those working 30 hours or more weekly for at least 50 weeks annually.

[30] Here, “Mainers of color” includes all Mainers who self-identified as anything other than White, non-Hispanic.

[31] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2011-15 5-year estimates.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] See Maine Center for Economic Policy, Census Bureau Data: Poverty among Blacks and African Americans in Maine Is the Highest in the Nation, Sept. 22, 2014. Web. Available at https://www.mecep.org/census-bureau-data-poverty-among-blacks-and-african-americans-in-maine-is-the-highest-in-the-nation/

[35] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2011-2015, 5-year estimates.

[36] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 1-year estimates, 2001-15.

[37] Jarosch, Gregor & Laura Pilossph, “The Reluctance of Firms to Interview the Long-Term Unemployed,” Liberty Street Economics (Federal Reserve Bank of New York), Aug. 3, 2016. Web. Available at: http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/08/the-reluctance-of-firms-to-interview-the-long-term-unemployed.html#.V6haDrgrKUl

[38] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015. 6.8% of respondents in poverty reported having a serious mental illness, compared to 3.3% of those above 200% of the Federal Poverty Level. For “serious thoughts of suicide in the past year,” the rates were 6.0% and 3.1%, respectively.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Krueger, Alan, “Where have all the workers gone? An inquiry into the decline of the U.S. labor force participation rate,” Brookings Institution, Sept. 7, 2017. Web. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/where-have-all-the-workers-gone-an-inquiry-into-the-decline-of-the-u-s-labor-force-participation-rate/

[41] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance Survey, 2015. Comparison of Mainers aged 18-64 with household incomes above and below $25,000.

[42] Ibid.

[43] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance Survey, 2015. For these purposes “low income” refers to Mainers with household income below $25,000.

[44] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015.

[45] Krueger, Alan, “Where have all the workers gone? An inquiry into the decline of the U.S. labor force participation rate,” Brookings Institution, Sept. 7, 2017. Web. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/where-have-all-the-workers-gone-an-inquiry-into-the-decline-of-the-u-s-labor-force-participation-rate/

[46] MECEP calculation based on Current Population Survey data. Comparison of male and female labor force participation rates for 12 months preceding May 2017 and May 2000.

[47] Sorg, Marcella, “Expanded Maine Drug Death Report For 2016,” Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center (Orono, ME, 2017). Web. Available at: http://www.maine.gov/ag/news/article.shtml?id=741243

[48] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Detailed Mortality file, 2000-2015.

[49] Case, Anne & Angus Deaton, “Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century,” Brookings Institution, Mar. 24, 2017. Web. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/6_casedeaton.pdf

[50] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Detailed Mortality file, 1999-2015.

[51] See e.g. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, health statistics. Web. Available at: https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=24879

[52] US Department of Health and Human Services, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data.

[53] US Department of Health and Human Services, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data, 2016.

[54] 50% of workers in Maine’s accommodation and food service sector worked for businesses with fewer than 50 employees; the same was true of 33% of retail workers. US Census Bureau, Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, 2015.

[55] US Department of Health and Human Services, Medical Expenditure Survey Panel, 2016.

[56] US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Quarterly Real Gross Domestic Product. Maine’s real GDP in Q1 2017 was unchanged from Q2 2006; Vermont’s GDP was up 0.5%, New Hampshire’s up 1.0%. National GDP was up 1.2% over the same period.