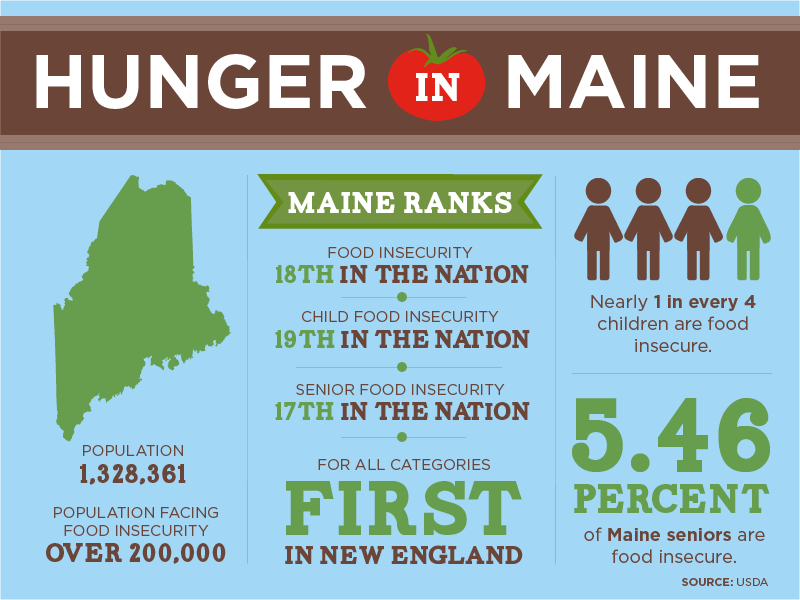

“Maine is the most food insecure state in New England. Five percent of seniors and nearly one in four children are food insecure in Maine. In 2013, 18 percent of Mainers used Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) at some point during the year. In Maine’s 1st Congressional District, where more than 40 percent of the residents are not eligible for SNAP, the overall food insecurity rate is still as high as 14.7 percent. More alarmingly still, in Maine’s more rural 2nd District, 72 percent of families are eligible for SNAP, while the overall food insecurity rate soars to 16.3 percent.”

July 30, 2015

Dr. Mariana Chilton, Co-chair

Robert Doar, Co-chair

National Commission on Hunger

Dr. Chilton, Mr. Doar, members of the National Commission on Hunger:

Thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today. I am Christy Daggett representing the Maine Center for Economic Policy, a nonprofit, non-partisan policy research organization. We provide citizens, policymakers, advocates, and the media with credible and rigorous economic analyses to help Maine people prosper. We testify today because hunger is the result of poverty and we offer solutions to address this in the broader state and national economic context.

Hunger in Maine

Food insecurity is fundamentally linked to economic insecurity. By supporting and expanding federal programs that sustain low-income families, we can ensure they have the resources necessary to put food on the table.

Food insecurity is fundamentally linked to economic insecurity. By supporting and expanding federal programs that sustain low-income families, we can ensure they have the resources necessary to put food on the table.

Maine is the most food insecure state in New England.[i] Five percent of seniors and nearly one in four children are food insecure in Maine.[ii] In 2013, 18 percent of Mainers used Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) at some point during the year.[iii] In Maine’s 1st Congressional District, where more than 40 percent of the residents are not eligible for SNAP, the overall food insecurity rate is still as high as 14.7 percent. More alarmingly still, in Maine’s more rural 2nd District, 72 percent of families are eligible for SNAP, while the overall food insecurity rate soars to 16.3 percent.[iv]

Recommendations

Eradicating hunger means addressing its root causes, which include low wages, poverty, and the accompanying family and community instability. Fighting hunger in a meaningful way requires creating and bolstering policies that promote more employment and better wages. In addition to increasing the federal minimum wage and indexing it to inflation, we recommend increasing the funding for and/or removing barriers to several federal programs that lift low-income families out of poverty and reduce hunger. These include SNAP, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Child Tax Credit (CTC), child care subsidies, and student meals.

Increase the minimum wage and index it to inflation

Decades of national wage data for all earners reinforce the same discouraging story: Real wages are flat or falling.[v] At the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, someone working full-time realizes an annual income of $15,080. This leaves a family of three (two parents and a child) $5,000 below the federal poverty level.[vi] Trapped in poverty, families must choose what expenses to cut, and all too often they can’t cover the cost of nutritious food. Increasing the federal minimum wage to $10.10 an hour would provide food security to approximately 29 million Americans.[vii]

Strengthen and protect SNAP

SNAP provides food for needy Mainers statewide. Congress must protect and increase funding for SNAP to ensure these families do not go hungry.

Nationwide, according to the USDA in 2013, over 60 percent of SNAP participants were children, elderly, or had disabilities. About 31 percent of SNAP households had earnings and nearly 43 percent of all SNAP participants lived in a household with earnings.[viii] For many of the poorest Americans, SNAP is the only income assistance they receive. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance, general assistance, and unemployment insurance are not available to millions of jobless households. In 2013, SNAP kept 4.8 million people out of poverty including 2.1 million children.[ix]

By design, SNAP costs rose substantially to meet the challenges of the severe economic recession and weak recovery in the last decade. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that by 2018, SNAP expenditures will fall back to their 1995 level as a share of the economy. In addition, CBO projects that SNAP expenditures will grow no faster than the economy in future decades, indicating that SNAP is not a factor contributing to the nation’s long-term deficit.

In Maine, our jobs recovery has been inconsistent, and stringent SNAP work requirements mean that 6,500 people in Maine’s most economically distressed counties lost their nutrition assistance this winter even though they are income-eligible and may be full-time job seekers.[x]

Though unemployment is declining statewide, thousands of Maine workers still struggle to find a job. Employment recovery in our three largest metropolitan areas: Portland, Lewiston, and Bangor –account for most of the improvement.[xi] In six of Maine’s thirteen rural counties, unemployment remains higher than the national average.[xii]

As many as 30,000 Mainers are working in part-time jobs because they could not find a full-time job.[xiii] As recently as last fall, the Maine’s Center for Workforce Research and Information reported that nearly 40 percent of jobs available were part-time or seasonal.[xiv]

Many of the jobs recovered in Maine are low-paying with few benefits and provide insufficient income to support a family. According to the Working Poor Families Project, 42.5 percent of Maine families have at least one member working and still fall below the federal poverty level.

It still takes many job seekers months to find a position. Nationally, 42 percent of the unemployed population in June had been unemployed for 15 weeks or longer.[xv] USDA data show that the typical individual subject to SNAP’s three-month limit has an income of 19 percent of the poverty line.[xvi]

Under many federal programs, Congress allows job search efforts to count toward work requirements. Adding this to the SNAP work requirement would ensure that unemployed workers, especially in Maine’s rural counties, will not go hungry while they are looking for a job.

Make EITC expansion permanent

The EITC reduces poverty, promotes work, and, for children in low-income working families, increases work hours and lifetime earnings. Families in Maine and across the nation rely heavily on the federal

EITC to make ends meet. Research shows the EITC’s impact on the well-being of poor children and their families is long-lasting. Reforms enacted in 2009 strengthened the EITC to reach more low-income working families. Unless Congress acts, these critical provisions will expire at the end of 2017, pushing more than 16,000 children and 34,000 Mainers overall into—or deeper into—poverty[xvii] and greatly increasing hunger.

Congress should also expand the EITC for childless workers. Low-income workers not living with and raising minor children currently receive little or no EITC benefit and are the sole group that the federal tax system taxes deeper into poverty. Some 64,000 childless workers in Maine are currently ineligible for an EITC[xviii] and face hunger issues as a result.

Expand child care supports and make the child tax credit permanent

Research has found that raising low-income families’ income when a child is young, not only improves a child’s immediate well-being, but also is associated with better health, more schooling, more hours worked, and higher earnings in adulthood.[xix] In Maine, child care too is a necessity for most families. For 70 percent of all Maine children under the age of six, both parents work.[xx] Child and child care supports are proven to increase employment, and working families are less likely to experience food insecurity.

We recommend that Congress make permanent the Child Tax Credit (CTC) that expires in 2017. Enacted in 1997 and expanded with bipartisan support since 2001, CTC helps working families offset the cost of raising children. It is worth up to $1,000 per eligible child (under age 17 at the end of the tax year) and includes a refundable component.[xxi] The CTC is a powerful weapon against poverty. In 2012, 60,000 Maine households received the refundable part of the CTC.[xxii]

The Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG) and the related Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) provides resources to state government to support families who can document that they need child care in order to remain working. Recent cuts in federal funding for the program mean that needy families are having trouble finding and affording child care providers. We recommend that Congress provide additional funding for child care subsidies to help working parents reduce their costs of day care so they can buy food for their families.

In addition, we would like to see Congress protect and strengthen Head Start and pass the Strong Start for America’s Children Act to help states fund voluntary universal prekindergarten services for low- and moderate-income children.

Continue federal support of student hunger programs

More than 46% of all Maine students are eligible for free or reduced meals. Yet, according to the Task Force to End Student Hunger in Maine, every day in our state an average of 51,619 students who are eligible for these meals don’t receive them. Barriers to utilization of this program include the necessity of an application to determine eligibility, the stigma of participation, and the timing of the program. [xxiii]

The federal government’s Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 is probably the most important program designed to reduce student hunger in decades. Its provisions, known as community eligibility, provides for schools in high-poverty areas to serve meals at no charge to all students without collecting meal applications thereby expanding low-income students’ access to school meals and reducing schools’ administrative burdens. It addresses many of the barriers identified by Maine’s task force. In school districts that have adopted community eligibility, more children eat breakfast and lunch each day.[xxiv]

We applaud Congress for this very important piece of legislation and urge its full implementation. We know that we still have some work to do to implement it in school districts where Maine’s neediest students live, but we recognize the importance of the program for reducing child hunger.

Although increasing participation in student meal programs is important, it is even more crucial to address the reasons these programs are so necessary in our state.

Addressing the underlying causes of hunger and investing in preventing it at the source is absolutely imperative. We believe our recommendations to increase the federal minimum wage, increase access to child care, and expand tax credits for working families will improve the economic prospects for Maine families and help make sure they can feed their families.

I thank you for your time and for your service. I am happy to answer your questions.

[i] Task Force to End Student Hunger in Maine. “Final Report,” January 2015. Accessed July 20, 2015. Available at: http://www.maine.gov/legis/opla/studenthungerreport.pdf.

[ii] Good Shepard Food Bank. “Hunger in Maine.” Accessed July 23, 2015. Available at: https://www.gsfb.org/hunger/.

[iii] U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Profile of SNAP Households,” March 2015. Accessed July 29, 2015. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/ops/Maine.pdf.

[iv] Feeding America. “Map the Meal Gap.” Accessed July 23, 2015. Available at: http://map.feedingamerica.org/congressional/2013/overall/maine.

[v]Desilver, Drew. “For most workers, real wages have barely budged for decades.” Pew Research Center, October 19, 2014. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/10/09/for-most-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/.

[vi] MECEP analysis of federal poverty data. Accessed July 29, 2015. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/15poverty.cfm.

[vii] Rodgers, William. “Food Security and the Federal Minimum Wage.” Rutgers University, November 2013.

[viii] U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Households: Fiscal Year 2013 (Summary), December 2014. Accessed July 29, 2015. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/ops/Characteristics2013-Summary.pdf.

[ix] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Policy Basics: Introduction to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),” January 8, 2015. Accessed on July 29, 2015. Available at: http://www.cbpp.org/research/policy-basics-introduction-to-the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap?fa=view&id=2226.

[x] Associated Press. “About 6,500 childless adult Mainers to lose food stamps on Jan. 1,” December 19, 2014. Available at: http://www.centralmaine.com/2014/12/19/6500-mainers-to-lose-food-stamps/.

[xi] Johnson, Joel. “Maine’s Labor Market Recovery: Far From Complete.” Maine Center for Economic Policy, April 2014.

[xii] Maine Center for Workforce Research and Information. “Unemployment and Labor Force.” Accessed July 23, 2015. Available at: http://www.maine.gov/labor/cwri/laus.html.

[xiii] FRED Economic Data. “Employed Involuntary Part-Time for Maine.” Accessed July 23, 2015. Available at: https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/INVOLPTEMPME.

[xiv] Maine Center for Workforce Research and Information. “Job Vacancy Survey Provides Unique Snapshot of Employer Demand.” Accessed July 23, 2015. Available at: http://cwri.blogspot.com/2015/02/job-vacancy-survey-provides-unique.html.

[xv] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “Unemployed persons by duration of unemployment.” Accessed July 23, 2015. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t12.htm.

[xvi] Bolen, Ed. “Approximately 1 Million Unemployed Childless Adults Will Lose SNAP Benefits in 2016 as State Waivers Expire.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 5, 2015.

[xvii] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Maine Fact Sheet: Tax Credits Promote Work and Fight Poverty,” June 30, 2015.

[xviii] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[xix] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[xx] Maine Development Foundation and Maine State Chamber. “Making Maine Work: Investments in Young Children = Real Economic Development,” January 2012. Available at: http://www.mdf.org/publications/Making-Maine-Work-Investment-in-Young-Children-%3D-Real-Economic-Development/475/.

[xxi] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Policy Basics: The Child Tax Credit,” December 4, 2014.

[xxii] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Maine Fact Sheet: Tax Credits Promote Work and Fight Poverty,” June 30, 2015.

[xxiii] Task Force to End Student Hunger in Maine. “Final Report,” January 2015.

[xxiv] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Summary of Implications of Community Eligibility for Title I,” June 30, 2015.